***

The Handyman's Guide

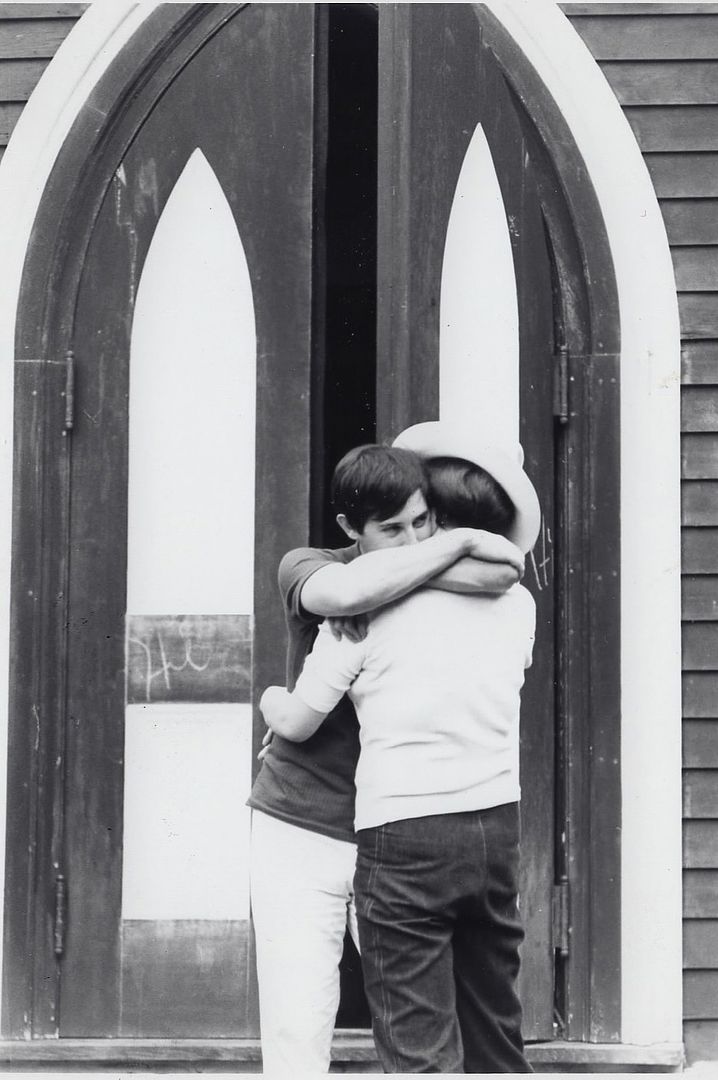

We had bought a little Church on top of a hill outside Woodstock in 1966 for $19,500, and it was my idea we

should restore it ourselves. He seemed to agree. At night after a day of stripping varnish and standing on a ladder staining tall window frames, we would lie in bed and Don seemed more fascinated by the "

New York Times Handyman's Guide," than by me. "Listen to this," he might say, "How to fix a dripping toilet."

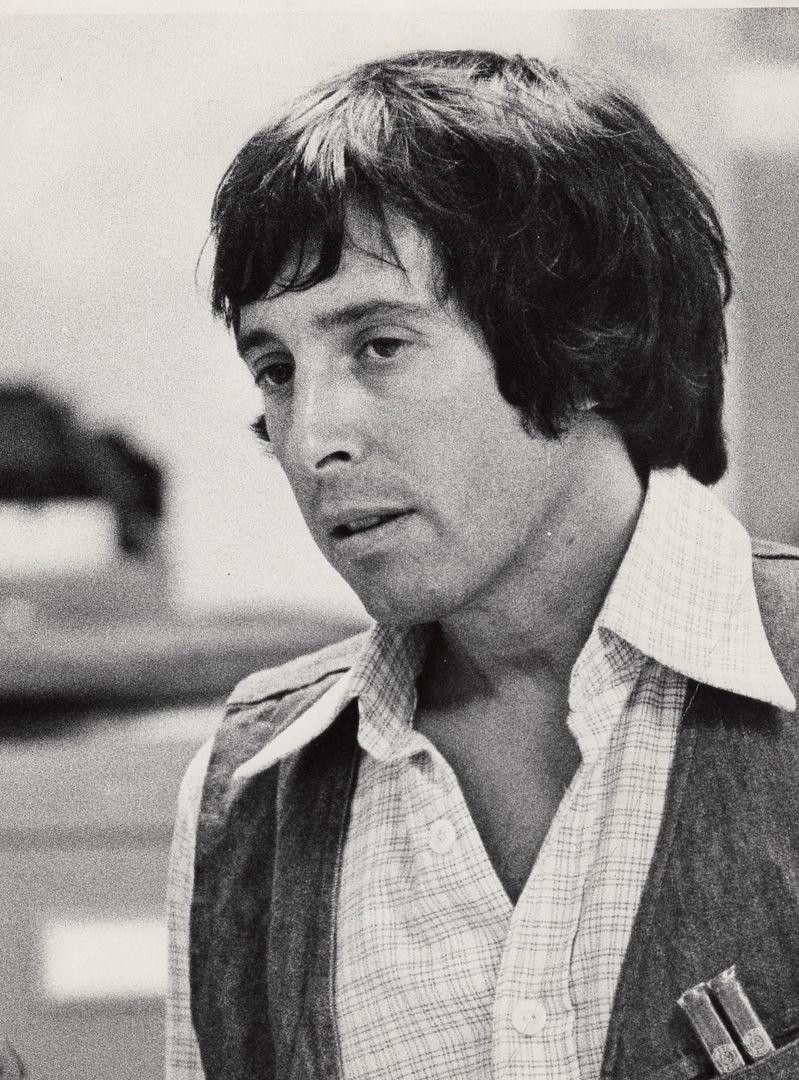

After the devastating strike that led to the near-death of his beloved Herald Tribune, he had little hope for the cobbled-together World-Journal-Tribune that emerged. He went directly to The Times.

City Editor Arthur Gelb decided Don should be the culture editor. "What shall I say are your credentials?" he asked Don.

Don pondered. "I played the clarinet in high school," he offered. Gelb waked him around introducing him to the critics.

"So what prepares you to be the culture editor?" asked Harold Schoenberg, the Pulitzer Prize-winning music critic.

"He plays the clarinet," Gelb responded.

One day Don stepped into an elevator with Gelb. "It's about the review of 'The Beard,' Don said. "You need to approve this. The review uses the word cunnilingus," he said, "because it seems that's what happens on stage."

"Isn't there a scientific word for that?"

Gelb asked.

"Yes," said Don. "It's cunnilingus." That's how cunnilingus first came to appear in The Times.

But such triumphs were few. "It's working for an insurance company," he mourned. And he quit, to go to Newsday, bringing Jimmy Breslin with him.

***

Joe Egg and I

One evening Don called to say he would be late coming home because he was going to see "Joe Egg" on Broadway a play I'd already seen and loved.

At about 8 the phone rang. It was Breslin. "Give me Forst," he barked.

I explained. Breslin was unusually silent but then, finally: "Well, have him call me."

Don had the

Playbill for Joe Egg in one hand when he

came home.

"How did you like it?" I asked.

"Very good," he said.

"There is no theater on Monday night," I snapped.

Her name was Ellen. She had invited him for dinner.

"What did she cook?" I asked.

"Lamb chops."

"Just lamb chops. Not even a vegetable." I tried to imagine this Ellen. Not even string beans.

"And then?" He'd only kissed her goodnight. I actually believed him. I was so in love.

***

Coming Apart

He was in love with a 22-year-old woman. We separated and came back together, separated again and came back again. After not one, but two, marriage therapists and his and hers psychiatrists, I finally had to admit our marriage was over when during a rare moment of making love, Don answered the phone, dropped my breast, and got lost in conversation with Breslin.

We shared the same lawyer, a disinterested fellow from the Bronx. I typed up everything we owned, marked each item with a "G" or a "D" mostly "G," and stapled it into the separation agreement. The wedding cash from my parents had seeded my brokerage account. He gave me the little church on top of the hill in Zena. I offered it to him on alternate weekends. He took one book, one record and three or four paintings. I paid to furnish his little third-floor walkup on Greenwich Street off Seventh Avenue. He chose country antiques -- some I really coveted -- not all that expensive in 1974.

It seems that in those years of washing the dishes while I cooked upstate, he'd picked up some technique. For his first brunch Don planned to steam lobsters. He called to ask how to make mayonnaise by hand.

"It's hard to describe over the phone," I said. "You can just add a couple of egg yolks and some mustard to Hellman's," I suggested. "I do that often. No one can tell the difference."

No, insisted Don the purist, suddenly a serious cook. He wanted to make mayonnaise on a plate with a fork. I did my best to explain. An hour later I had finished my work.

"Do you want me to come down and do the mayo for you?" I asked.

"It's done already," he said.

***

Checking In

In the next 40 years one or both of us were occasionally caught up in much joy or intrigue or professional obligations or, in my case, travel. There might

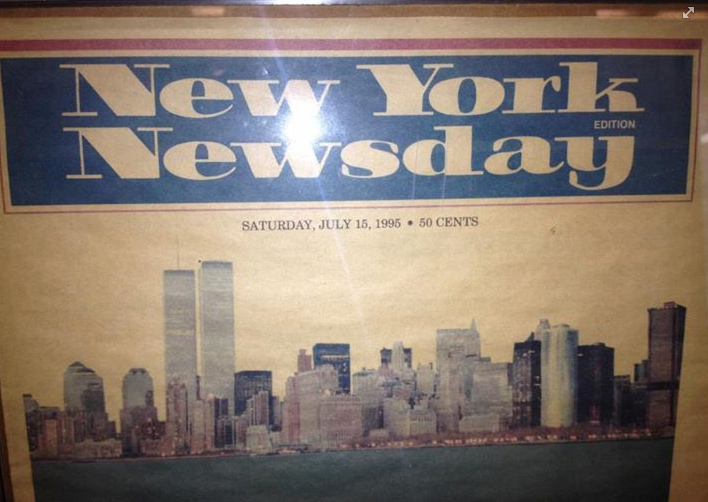

be months between conversations. But we always stayed in touch, exchanging news of triumphs, emotional blips, catastrophes, passions. I knew he'd met and was mesmerized by a brilliant photographer named Starr Ockenga. I heard how a cereal guy had killed New York

Newsday. How Don had broken down and wept half way through the task of firing 100 people. I sympathized with how restless he was running the Queens edition of

Newsday.

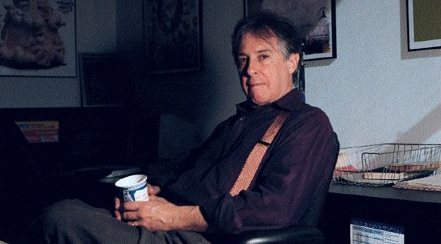

He called to trumpet his clever maneuvers in turning a headhunter's phone call into a job for himself at the Village Voice. How he had persuaded the Voice owners they needed a 64-year-old professional newspaper man to run the paper, not the 30-year-old boomer they'd been searching for.

In recent years, I'd begun to think of us as foul weather friends. When one of us was in trouble, we talked. He was pessimistic about a new team buying the Voice and took his severance, hoping to find another newspaper job. He moved to the country house in Livingston with Starr's legendary garden and discovered he loved teaching journalism at the University of Albany.

He amused me with tales of his unique teaching methods that amused him and, reportedly, most of his students.

He called to see how I was holding up when my guy Steven was diagnosed with inoperable cancer. He let me rant and rave about life in our tiny apartment set up as a hospice as the number of aides multiplied.

I only invited Steven's friends and collectors to the celebration of his life and work several months later. I regretted that Steven was not there to see the slideshow, hear the moving words of friends, approve the mini grilled cheese sandwiches and taste the margaritas (he was dead so the tequila would not have been forbidden.)

I had decided to make a celebration for my 80th Birthday with roasts and toasts, like a memorial service, except I'd be there to enjoy it. Don promised he would come.

But then excruciating pain at 4 a.m. He had been stupid, Don told me, not to have a colonoscopy for ten years. He met with the surgeon. I wanted him to see a doctor at Memorial Sloan Kettering. He would not discuss it. The hospital was excellent, he said. The surgeon was brilliant. The oncologist was thoughtful and kind. I realized I didn't have a say here.

I didn't want him to do chemotherapy. It's a killer. They kill you in hopes it will cure you. I wanted him to go directly to the new less stressful targeted therapy, still in trial. But that was a dream. He wasn't eligible. It wasn't my business. He was so confident. So full of bravado. "It sounds crazy, I know, but I'm almost looking forward to the fight," he said. It would be tough but he was sure he could beat it.

I called him often. He reported in with the ups and downs of starting chemo. When I came back from New Year's Eve with friends in East Hampton, it was snowing and I didn't get into my office till January 2nd. There was Don on the answering machine: frantic rasping messages, cries for help, his voice fading in and out. I called the house. I called his cell. I called the cell again. Terrified. Waiting.

"Who is this calling?" he asked, a rasping voice responding to my message on his cell some time later.

"It's me Don. Gael."

"I'll have to call you back." He was in the emergency room in Hudson. He handed the phone to girlfriend Val. There was a blizzard. She had no snow tires. He was in trouble. He wouldn't admit anything was wrong. He was over-chemo'd. He was as white as a sheet. She'd had to bully him to get him into the car.

I won't go into the play-by-play. I won't burden you and torture myself reliving the series of steps and missteps that brought him there. I won't go over the stubbornness, the indifference, the incompetence, the mean tricks of timing, the magical thinking that conspired against him. He was already as good as dead when they bundled him into an ambulance in Hudson to ride the closed highway to the ICU of the Albany hospital where he'd had his surgery. Was it seven doctors who worked on him? Or nine? A tag team of doctors from every department. Well, they tried.

His trainer relaxed in the gym on the reclining bike waiting for him to arrive at the very moment he was dying.

"I've never felt better in my life," Don had told him the week before. Pumped up, exhilarated, determined.

He wasn't gong to die.

He was going to live forever.

***

Donald H. Forst, Feisty Newspaper Editor, Dies at 81.

Click here to read the

New York Times obituary by James Barron.

***

Today's colors are black and red. Black for the sadness. Red for the red and white checked shirt, my favorite of Don's custom made shirts in the 60s. He'd become quite the dandy, counting on me to set out his suit in the morning and chose the shirt, a tie, the cufflinks and a silk pocket hanky, red but not ever matching. He wore it poufed.

Click here to return to FORKPLAY archives.