Leadership+Design

"We design experiences for the people who create the future of teaching and learning."

In our work, we build capacity, create conversations, and make connections.

Follow us on:

|

|

Upcoming Programs:

Santa Fe Seminar

November 11-14, 2015

La Fonda on Plaza

Santa Fe, NM

SOLD OUT

Trailblazer

June 27-30, 2016

Watershed School

Boulder, CO

L+D XQ

A year-long professional learning adventure. Beginning summer 2016.

|

|

Leadership+Design

Collaboration Cards

Order your deck today.

This card deck is a tool to enhance group work. The paradox of group life exists in any group - those that form in places of business, schools, churches, sports teams and even families.

As human beings, we crave group life and we also find it to be hard, messy and complex. Groups that have tools to identify and manage conflict, to get "unstuck" and to move forward, are more productive and also more joyful.

These playful L+D Cards offer over 70 suggestions for managing group life, increasing productivity in groups and deepening the connection between collaborators.

$25.00 per deck + Shipping and Handling. Click on the icon below to place your order.

|

|

L+D Board of Directors

Ryan Baum

VP of Strategy Jump Associates

Lee Burns

Headmaster

The McCallie School

Chattanooga, TN

Sandy Drew, Board President

Development Consultant

Sonoma, CA

Matt Glendinning

Head of School

Moses Brown School

Providence, RI

Trudy Hall

Head of School

Emma Willard School

Troy, NY

Brett Jacobsen

Head of School

Mount Vernon Presbyterian School

Atlanta, GA

Barbara Kraus-Blackney

Executive Director

ADVIS

Philadelphia, PA

Karan Merry

Head of School (Ret.)

St. Paul's Episcopal School

Brooklyn, NY

Carla Robbins Silver (ex-officio)

Executive Director, L+D

Los Gatos, CA

Mary Stockavas

CFO

Bosque School

Albuquerque, NM

Paul Wenninger

Interim Head of School

Alexander Dawson School

Las Vegas, NV

Christopher H. Wilson

Head of School

Esperanza Academy

Lawrence, MA

|

|

|

|

| Want Great Design? Get Great Feedback. |

|

Greetings, Friends,

As you may remember from last month's newsletter, throughout the year, the Monthly Recharge will feature one habit, skill, or mindset of successful leaders, learners, designers and innovators that you can practice and develop in your work. This month we are focusing on giving and receiving feedback.

On a scale of 1-4 (with 4=high and 1=low), how strong is your school's culture of feedback? Just go with your intuition on your answer. How often do the adult professionals in your school community seek feedback? How authentic is the feedback when it is given? How do community members receive feedback?

If you answered 4, stop right now and email me with exactly how your school is achieving a culture of healthy feedback. What are the conditions that exist in your school that support open, honest and regular feedback. What is your secret sauce? I want to know.

If you answered 3 or below, think for a moment about what might need to change in your school to promote better, regular, ongoing feedback which will drive your school to serve students better, run more efficiently, and be a more place for learning, teaching, and leading.

Giving and receiving, feedback is, at its core, evidence of being a  lifelong learner, a quality that many of us have in our mission statements. We expect our students to accept feedback all the time - feedback in the form of grades, narrative comments, red marks on essays, and in the daily, more informal assessment we give to them in class. But are we ever as readily receptive as an adult community to disrupt harmony by giving and receiving authentic feedback ourselves to each other? lifelong learner, a quality that many of us have in our mission statements. We expect our students to accept feedback all the time - feedback in the form of grades, narrative comments, red marks on essays, and in the daily, more informal assessment we give to them in class. But are we ever as readily receptive as an adult community to disrupt harmony by giving and receiving authentic feedback ourselves to each other?

In my mind, a solid 4 rating means that your adult professional embraces feedback, both formal and informal and has strong systems and processes in place that encourage feedback - things like annual faculty, parent, and board surveys, intentionally designed evaluation processes for students, faculty, staff and leadership that happen at minimum annually, but even better quarterly, regular audits of programs, curriculum, pedagogy, time and space. Other good signs that your culture supports feedback might be meetings that end with questions like, "How are we working together as a team/department?" and "What can we do to get better at this work?" and school leaders who ask their reports with genuine curiosity, "What can I do to better support your work?" "What do you think about this idea?" or "How did this meeting go for you?"

What if you spent a week "playing anthropologist" with the following question in mind: "What evidence do I see that our adult community has a strong culture of feedback?" Like a professional anthropologist, carry around a field notebook and document moments of both formal and informal feedback. Spend some time with colleagues. Ask them questions about their classes. See how many times you hear someone ask questions like: "What do you think about this?" "Will you come by my class and let me know what you think about this lesson I am teaching?" "How can I/we do this better?" Attend meetings with this question in mind. How receptive are team members to feedback they get in meetings? How good are they at giving feedback? When someone or committee presents an idea or project they are working on - whether it is a new course or lesson, a new schedule, a meeting agenda, or a draft of a mission statement or other core institutional work, how precious is their draft or how willing are they to listen to new suggestions?

We can learn a lot about both good and bad feedback from the

design community. "You cannot have great design without great

feedback," begins Scott Berkum in his talk Feedback Without Frustration. This 15 minute video offers some key habits and practices that designers (and educational leaders in their roles as experience designers) can adopt in order to make feedback more meaningful, especially when presenting a new idea or product and much of which can be applied to feedback - both formal and informal. A few tips include:

- taking responsibility for the feedback you are getting

- going after the kind of feedback you want

- having a designated facilitator for more significant processes

- having goals for the project that you can use to make the feedback more helpful

- not confusing what you like/don't like with what is good/bad

- (most importantly) just getting better at talking to each other.

Designers also know how to use prototypes of various fidelities to

get feedback often, leading to iterative process that are more likely to produce ideas that stick. Sometimes the best thing you can do is to show someone a rough sketch of your idea - the Dan Roam "back of the napkin" approach. Before you get too wedded to an idea and it becomes to precious to change, build a low fidelity model or two, test the initial concepts with a few people and iterate. Don't get lulled into the "dog and pony show" Scott Berkum describes, where getting feedback is really just a self-gratifying, self-congratulatory moment. When you ask for feedback, want it and mean it.

I've learned a lot about giving and receiving feedback from my colleagues Greg Bamford and Tim Vos who have articles featured in this month's newsletter and I am sure you will too. The two greatest lessons I have learned are that 1) Giving and receiving feedback is a habit and skill that great leaders can practice and improve their capacity over time. You don't have to be skilled at first, but you can get better if you work at it 2) Remembering to leverage your humanity when you are giving and receiving feedback. Even the most critical and direct feedback can be delivered humanely.

L+D has some exciting things on the horizon and we are already planning for summer and beyond, so check out our website for the latest and greatest and for those of you already considering our Trailblazer Conference in Boulder with our amazing school partner Watershed School, registration is open so register up now. It will sell out - I mean who doesn't want to spend four days in a beautiful spot with interesting colleagues working towards educational innovation? And for the bold and adventurous school leaders out there, L+D is announcing our new Experiential Quarterly (L+D XQ). We are so exited to offer something for schools and school leaders that reinvents the professional learning experience and can allow us to work more deeply with those schools that what to make significant progress on a goal or initiative. We are only offering this to a very small group of school leaders this year, but if you think you might want to learn more about joining this program in future years, please contact me.

Warm regards,

Carla Silver

Executive Director

Leadership+Design

|

Building a Culture of Feedback Starts With You

|

Timothy Vos,

Leadership+Design Collaborator and Site Director of L+D Summer, Seattle

|

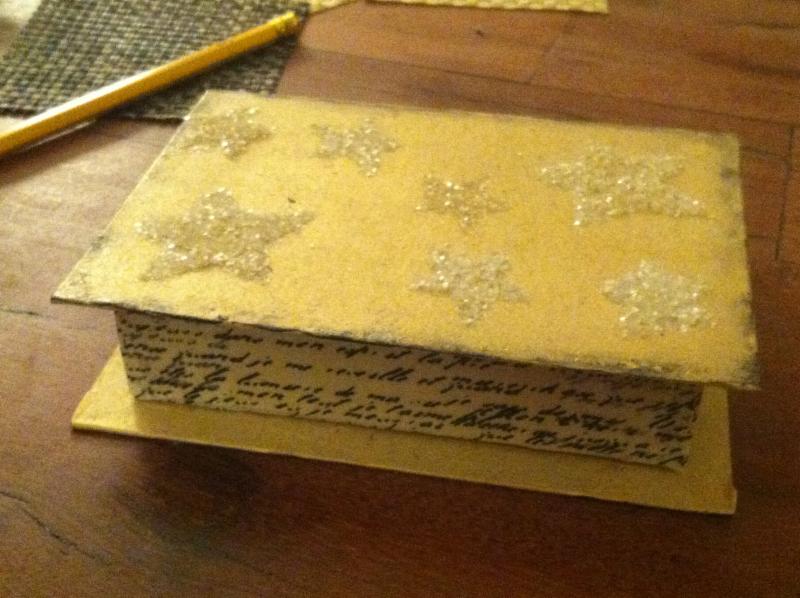

I have little gold-colored paper box on my desk that has stared at me every day for three years. It's a box filled with  compliments. And it's never been opened.

Several years ago a colleague sweetly sent a request to all the teachers I had mentored and asked them to write a compliment to me. Each was to start with the sentence, Tim is my hero because... She printed the notes, cut them into strips of paper, placed them in a home-made box and gave them to me as a holiday present. And I can't get myself to read them. I once confessed this to my wife who accurately called this behavior absurd and not very gracious. And while, rationally, I agree with her, emotionally, it's a struggle to open the box. While the intention was certainly to make me feel important, I suspect my fear with opening a box of conscripted compliments is that they would make me feel trivial - Thanks for helping me understand the district acronyms. Or they would lack authenticity - Thanks for giving me good ideas. Or they would be yearbook inscription material - You're great! Stay cool! HAGS!

I can't say I fully understand my allergic reaction to compliments, but I suspect it's related to the paradoxical nature of feedback. In their insightful book, Thanks for the Feedback, Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen argue that feedback is often hard to take because feedback lives at the crossroads of two fundamental human needs - the urge to learn and grow AND the desire to be accepted and belong. So even when we get feedback that satisfies one of those needs, it inflames the other.

The authors argue that feedback is additionally painful because most of us are really clumsy at giving it, and even the best feedback is often ineffective. For example, a friend and accomplished "feedbacker" noticed that a teacher was sending emails at 4:30am. He sent her a note acknowledging the early hour, wanting to show her that he was noticing her hard work. Her response was, Why are you scolding me? Stone and Heen conclude that the key to building a healthy culture of feedback shouldn't depend so much on us getting better at giving feedback, as conventional wisdom might suggest. They argue the key is getting better at receiving feedback. And that begins with you.

After reading Stone and Heen's book for L+D Summer Program 2014, I asked each of the teachers to join me in writing a Feedback Manifesto, a set of intentions around feedback. My manifesto was largely built around how to make feedback less painful, and included these 3 goals:

Ask for feedback sooner rather than later - Be the windshield, not the bug.

My thinking here was that part of the pain of feedback is that it is often a surprise. Nothing makes the heat rise on my neck more quickly than getting honked at, and I think it's because I'm unprepared for the feedback. So I decided, instead of waiting for it, I would begin asking for feedback, rather than waiting for it. When a teacher confessed that I made her anxious when I visited her classroom, not only was I able to keep a stiff upper lip, but I also got valuable information to act on before it became a more significant issue.

Ask for it more frequently - Death by a thousand cuts is not just a clever phrase.

My hunch was that more frequent feedback would lower the stakes. When your supervisor, principal, or head only observes you teaching a few times a year, the stakes feel high. If the feedback doesn't register with what you were expecting, it's easy to give it a wholesale rejection and not learn a thing from it. It's also just as easy to internalize it and lose your confidence. Over the course of last year, I did discover that getting feedback more frequently gave me more data points and hence a more accurate picture of my work. It also helped me avoid obsessing over the outliers. Additionally, I discovered that hierarchy and position can get in the way of authentic feedback. A friend who teaches at a university complained to me that he could not get quality feedback from his junior colleagues despite repeated requests. I found direct requests for feedback to be limiting at times as well and had better luck conducting empathy interviews to solicit meaningful feedback. A simple question like, Tell me about your experience so far at this school/in this program, often reveals much more than, How did I do?

Respond with a gratitude - If you can't say anything nice... say thank you.

My theory this time was that a big part of the discomfort of feedback is not knowing how to respond. Oftentimes, when offered an unwelcome scrap of feedback, I will get defensive and start explaining myself or my idea. Other times, I will get apologetic and wear the feedback like a giant red A. Either way, I feel crummy afterwards. Saying thank you sounds both gracious and confident. I'm reminded of a time last year when I asked for feedback on a movie I was making of students showing appreciation to their teachers. I was

really excited about the project, creating an imitation black and white, silent movie, telling a story through expressions and gestures. Trying to live up to my feedback promise, I showed my working copy to a colleague. She said she liked it but she wished she could hear what the students were saying. In my head, I was screaming, really excited about the project, creating an imitation black and white, silent movie, telling a story through expressions and gestures. Trying to live up to my feedback promise, I showed my working copy to a colleague. She said she liked it but she wished she could hear what the students were saying. In my head, I was screaming,"Essentially, the thing you don't like is the ENTIRE CONCEPT OF THE MOVIE!! HOW IS THAT HELPFUL??" But what I said was, thank you for the feedback.

Saying thank you is more than saving face, it's assuming best intentions and seeking to understand. Instead of just rejecting the feedback or adopting it, I asked myself, "How can I make a silent movie where one can hear the kids' voices?" It led me to seek out and watch Buster Keaton and Little Rascals movies. I learned how to re-sequence the clips to allow kids' inaudible voices to be heard. While I hated hearing it at first, it was the most valuable feedback I received. Saying thank you instead of reacting gave me the time to sift through the feedback and find the hidden value in it.

Building a culture of feedback begins with you. It takes time, faith and forgiveness, and begins with cracking open the little gold box. Treasures await.

|

| Bad Feedback? Get Curious. |

|

Greg Bamford, Head of School, Watershed School and Co-Founder, Leadership+Design

|

When I am asked how I feel about feedback, I will say what I'm expected to say: I love feedback. Love, love, love. Bring it on!

What I truly mean when I say I love feedback is this:

- Feedback is vital to growth, and I always want to get better;

- The gap between how I perceive myself and how others experience me is always present, and feedback offers a way to narrow the gap;

- Leaders more often fail because of what they don't know about themselves than because of what they just don't know.

And yet: how does it feel when someone tells you, "I'd like to give you some feedback"?

What happened in your stomach? Did it feel good?

I mean, really. You work so hard. Your intentions are so good. And no matter where you are in the organizational hierarchy, you're likely to feel underpaid. Don't these people really understand everything you've done for them?

Let's outline the ways in which feedback can fail: - Much of the feedback you get as a leader is rooted in untruth. Rumors spread, and then people offer feedback about what they heard you did. There's nothing to do but to feel frustrated.

- A lot of feedback is vague. It's about what you do in general,and without examples. As a result, there's no clear path forward.

- Feedback is contradictory. As a school leader, there are always multiple points of view in any faculty meeting or parent coffee. You can't make everyone happy.

- Rather it is often a recitation of what you should have done, with hindsight, given unlimited time and resources. They're not in the situation; they don't see the tradeoffs; and they speak with the perspective of what worked or didn't work with your first attempt.

The challenge of growth as a school leader is bridging the gap between one truth and the next: on the one hand, much of the feedback you get is irritating, poorly delivered, or wrong; on the other, it's the only thing that can make you better.

And while people can get better at delivering feedback, many of the people you interact with - Board members, parents, alumni - are difficult to coach.

As a Head of School, I love great feedback. But poor feedback frustrates me as much as anyone. And in the end, what I've realized is that it's my job to receive feedback differently. When you get feedback, it's time to get curious.

I've found that having a script can help me navigate these moments. - "Tell me more." If nothing else, this is an opportunity for them to be heard. But by employing the classic questions that drives empathy in a design process - why? - you can understand the assumptions behind their question.

- "What would success look like next time?" This shifts feedback into an articulation of a future vision - one you can work towards together.

- "What I hear you saying is..." Often, what makes feedback hard to receive is an assumption that you're making about the other person's comment. Checking for understanding ensures they feel heard - and checks your own assumptions about the other person's intent.

As Leadership+Design's co-founder, Ryan Burke, often says, 50% of what people say isn't about you - it's about them. Taking the time not to resist feedback - but to get curious - allows us to receive feedback in a better way.

|

|

|