HALF PRICE FLACs

|

| |

All FLACs of this release 50% off for one week only

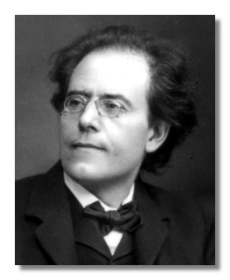

MAHLER

Das Lied von der Erde

Kathleen Ferrier

Julius Patzak

Vienna Philharmonic

Orchestra

Bruno Walter

Recorded in Vienna in May, 1952

CLASSIC REVIEW

This, of course, is the most famous studio recording ever made of Mahler's great symphonic song cycle. It's currently available on a reissue by the nominal original label, Decca 466576, as well as on Regis 1146. The latter disc also contains a Ferrier performance of the Brahms Alto Rhapsody with Clemens Krauss and the same orchestra from 1947. Yet this is as demonstrably superior in sound quality to either of those as EMI's most recent issue of the Klemperer Mahler Fourth (67035) is to any other previous edition.

The reasons will be obvious to anyone familiar with this recording from the very first notes. The sound is fuller, more natural, and less edgy on the top end than any past or present CD incarnation. About a quarter-century ago, at the dawn of the CD era, I owned this on a different Decca issue, but eventually gave up on it because, although the sound was clear enough to allow you to hear the stays on the oboe, it was also slightly uncomfortable to my ears.

For me, personally, this is the best of the four Walter performances I've heard, the others being Thorborg/Kullmann (1936); Ferrier/Svanholm, with the New York Philharmonic (1948); and Forrester/Lewis from 1960. It's one of his swiftest readings, coming in under an hour, and actually less romantic in feeling than Otto Klemperer's supposedly non-romantic recording from 1965. But it is not my all-time favorite reading of the score, great as it is. That honor goes to the little-known 1939 Dutch broadcast by Thorborg, Carl Martin Öhmann, and the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Carl Schuricht (Bel Age 15). For me, Schuricht conducts the most intense and texturally transparent reading on records, bar none; the 1939 sound quality is absolutely stupendous for its time; and Öhmann is the finest tenor soloist I've ever heard in this work. (I should also mention that my favorite stereo/digital reading is the out-of-print DG disc with Brigitte Fassbaender, Francisco Araiza, and Carlo Maria Giulini conducting the Berlin Philharmonic, a recording savaged by critics for reasons I could never quite fathom. Despite slower tempos, Giulini's pacing and shaping are simply magical, and the way Fassbaender's voice melts into nothingness in "Der Abschied" still sends chills down my spine.)

But back to this Das Lied. Julius Patzak was a very great artist who was simply not born with a great voice. Even in the best of circumstances, its tone was thin and rather colorless, yet to listen to the intelligent way he sings here is to understand why both Walter and Furtwängler admired him-also why he was considered a great Florestan in Fidelio, despite having a very small, un-Florestan-like voice. Ferrier, on the other hand, had one of the great voices of all time. Relistening to her, I was struck by how much she, like Louise Kirkby-Lunn and Helen Watts, sounded like a German contralto. Her low range is so effortless as to almost sound bottomless: she sounds as if the voice extended at least three notes further down than the lowest note she sings. Her interpretation, particularly in "Der Abschied," has always been a matter of personal taste (she does not really sing softly in all the passages marked as such, but in fact sings out forte on certain notes), which for me discounts it slightly-but only slightly-in comparison to the other recordings I've named. But omigod could she sing. No one, in my memory, imparts such geniality and lightness to "Von der schönheit" as Ferrier. Here, no one can touch her, not even Thorborg or Fassbaender.

The Vienna Philharmonic, like the New York Philharmonic, always had Mahler "in its blood," so to speak, and they play their hearts out for Walter here. One little thing I noticed which I'd forgotten: the solo violin in "Der trunkene in Frühling" plays with much more portamento than we're used to nowadays.

If you admire this recording as much as I do (or more), this is clearly the pressing to own. The restoration is nothing short of magnificent.

Lynn René Bailey

This article originally appeared in Issue 32:2 (Nov/Dec 2008) of Fanfare Magazine.

ALL FLAC DOWNLOADS OF THIS RELEASE ARE HALF PRICE FOR ONE WEEK: PASC 109

NB. Offer does not apply to CDs or MP3 downloads

|

REVIEW

|

2. John Sunier

1. How does one improve upon what has already passed as a "Great Recording of the Century"? Walter Gieseking (1895-1956), born in Lyon, France but German by temperament, became renowned for his exquisitely transparent touch and canny pedaling, a master of the French Impressionist repertory. Whether Gieseking's "French" style could claim "authenticity" remains debatable, since Alfred Cortot's inscriptions, for instance, occurred after his technique had deteriorated drastically. One might ask for the more sec Robert Casadesus readings to return to us for comparison. Gieseking recorded the complete Debussy Preludes for EMI 12-16 August 1953 (Book I) and 9-10 December 1954 (Book II). Critics complained that Gieseking's piano tone sounded muddy, and that Gieseking, with his penchant for sight-reading, had often departed from Debussy's printed notes. Prior to WW II, the Gieseking of the 1930s presented a volatile, impulsive interpreter, far afield of the "serene" master Walter Legge sold to the public via EMI. But Andrew Rose has brought a new spaciousness to the EMI inscriptions in these remasterings, even to the point of the pianist's breathing - problems with his adenoids - while he executes one of the great feats of keyboard wizardry for posterity. At the time of their release, perhaps only the readings by E. Robert Schmitz could compete artistically. But even the severest critics could only marvel at Gieseking's ability to pedal a phrase to infinite degrees of nuance in order to release the secrets in the music which he truly cherished. [One critic summarized the art of both Debussy and Gieseking as "expressing the inexpressible."...Ed.]

There are too many special "moments" in these performances to enumerate them all, but the opening Delphic Dancers conveys an especial ethos, even given some rhythmic irregularities. So, too, Gieseking yields to the temptation to speed up the middle section of La cathedrale engloutie, although the majesty and "Wagnerian" mysticism of the piece rises and sinks with resonant power. The various "wind" pieces - Le vent dans la plaine and Ce qu'a vu le vent d'ouest - offer a rare combination of measured tempos and underlying tension. The capricious side of Debussy does not escape Gieseking, as in La danse de Puck, General Lavine: eccentric, Minstrels, and La serenade interrompue-pieces in which Gieseking's feathery touch and pearly play add a sardonic wit and vitality to the metric subtleties and parodies of which Debussy is capable. Voiles and Des pas sur la neige gain a new eeriness, a sense of anxiety and detached angst in their use of whole-tone scales or passing atonality. The energetic pieces, like La Puerta del Vina and Ondine evoke a vibrant color line in the keyboard similar to what Stokowski and Celibidache achieve in orchestral tissue. The more parlando exercises, such as Les collines d'Anacapri, Bruyeres, and La fille aux cheveux de lin exemplify Debussy's incorporation of plainchant and Massenet's pure melos into a new alchemy that Gieseking realizes with disarming simplicity of gesture. Gieseking's art instills in us that sense of "a miracle of rare device" a true master can project. That the entire project may be subject to occasional objections we do not contest, but Gieseking provided a template for these preludes: vigorous, sensitive, and passionate, that has stood the test of time with honor. The new Pristine incarnation (in any format version) deserves to be included in any piano collector's library.

****************

2. (This will be mostly technical stuff for hi-res connoisseurs, so you fans of decent historical recordings of music needn't read further.) I was quite surprised to see that Andrew Rose at Pristine Audio had released his own remastering of the Debussy Preludes by Walter Gieseking, even though after many other reissues on theirs and other labels, EMI Classics had issued the Preludes as part of the non-quite-Complete Solo Piano Music of Debussy on SACD last year! (I don't have any of the Debussy reissue CDs, but I do have a double-disc of Gieseking's Ravel piano music of about the same vintage on the Allegro label. It is quite distorted on peaks and wooden-sounding.)

As you can see by the review, I was quite impressed by the improvement in the fidelity of these early 1950s mono recordings when issued in the SACD format. Part of my interest was piqued by page 10 of the hardbound booklet of notes with them, which goes into detail on the steps that Simon Gibson and his crew at EMI went thru to bring their many years of experience remastering archive recordings from the original analog sources to release on SACD. They checked all the notes on the original recording job files, played the tapes on their re-calibrated Studer A80 open reel tape machine, and used a Prism converter and SADiE Digital Audio Workstation to transfer the analog materials to 96K/24-bit digital audio files. They also decided whether or not to use CEDAR audio restoration software to get rid of any clicks, hiss or pops. They then added recorded reverb in the spaces between tracks where before there was just paper leader tape. The final result was equalized and then converted to the required CD or DSD formats to master the hybrid SACDs.

In spite of all of this effort, Andrew Rose has clearly improved upon the first SACD in the EMI Debussy/Gieseking set, making me wish he also made the other three discs so available. Using the latest of various softwares which he calls "32-bit XR Remastering," he laboriously goes thru the entire source material, not only controlling objectionable noise but also equalizing for the most pleasing and natural musical sonics. It is not revealed whether his source material was vinyl, tapes from EMI, or the EMI SACDs, but the original two LPs were released on the Columbia label, one for each Book. I think one of the primary subtle enhancements here is Rose's use of the Capstan software, which has only recently become available, and corrects for even the most minute speed variations in the original analog sources. Remember how those audiophiles of us who were pianists or heavily into piano music appreciated even the first compact discs, in spite of their not equalling the overall sonics of vinyl? It was because of the rock-steady timing, which even the best lathes and turntables failed to provide. The pacing (if the original recording was digital) had absolutely no flutter or wow due to the timing clock which is an integral part of digital recording. Even some expensive turntables of the time had flutter and wow problems which were later improved by accessory speed control boxes which corrected the varying AC power. (I recall when I originally got my SOTA that had been acclaimed in the audio press; I said "This sounds terrible!"). I would be curious to know if they had replaced the falling weights used to operate the cutting lathes at EMI in the 1930s and '40s with electric motors by the time Gieseking was recording in the early '50s, but even the very best analog masterings can suffer from some slight speed variations.

Since the highest-res format that Pristine Audio offers customers is 48K/24-bit (with the escalation from 16-bit to 24-bit the main reason for the greatly enhanced fidelity), one cannot burn a standard CD-R with the hi-res downloads from their site. You must burn the FLAC files to a DVD-R, either directly as FLAC files or converted to PCM, WAV or AIFF files. In the latter two cases you will be losing the hi-res resolution by conversion to 44.1K/16-bit audio files. My Oppo BDP-95 deck plays FLAC files, and the best sonics are achieved without having to make any conversions, so I just burned a DVD-R of the FLAC files. (I'm planning to stick with the physical discs.) My Mac will not even play these files since Apple would like FLAC to just disappear, and the makers of a plug-in to play at least standard 44.1/16 FLAC files have not seen fit to issue an update to their software for the Mt. Lion OS. (There are more suggestions on the Pristine site.)

It wasn't possible to do a quick A/B comparison of the EMI SACD with Pristine's hi-res FLAC remasterings, because I needed to use the video display to navigate to the tracks on the DVD-R. (Next time I'll just drag all the tracks over to burn, rather than leaving them in the folder, which evidently caused the problem.) I compared a number of the two dozen tracks between the two discs, on both my AKG K1000 headphones and my Von Scheikert left and right frontal speakers. (Gary Lemco reviews the standard CDs on a one-box CD player.) The SACD was nice, but next to the Pristine remasterings, the piano was rather wooden-sounding and somewhat opaque. There was little acoustic space around it, and some overtones to the music were missing. (Of course the CD layer on the hybrid SACD sounded even more wooden when I selected that layer.) Geiseking was known for the amazing dynamic range he could achieve in the Debussy piano music, and that is audible here, but not nearly as much as on Pristine's remasterings. (As someone has observed, the French have been pissed that probably the greatest interpreter ever of Debussy's piano music was in fact a German.)

On the EMI SACD there is considerable distortion to be heard on even the medium-volume-level notes of the Preludes, but on the Pristine remastering such distortion is only heard on the high volume peaks, not almost continuously. There is a greater degree of dynamic range that frequently turns the piano into the closest approximation of an orchestra that any composer has ever achieved in his piano music. The sonics are not at all wooden, with a very natural ambience and clarity that, tho mono, sounds as if it could have been recorded recently rather than in the early '50s. I don't know if Gieseking was partial to the Steinway as most concert pianists are, but I can hear a bit of the steely Steinway treble that causes me to prefer Boesendorfers and Fasiolis on recordings that are well made.

To take a specific track, there is No. 16 in Book 2: "The Fairies are Exquisite Dancers." The EMI SACD has a great deal of distortion thruout, but in the Pristine 48/24 remastering it is nearly all gone, only being noticed on the extremely loud climaxes, and there is a slight depth apparent in the piano sound, missing on the SACD. (Pristine doesn't offer this one in their Ambient Stereo option, which can add considerably to mono orchestral recordings.)

| |

|

|

|

CONTENTS

| |

This Week Bruno Walter's 1938 Mahler 9

Walter Fred Gaisberg on the conductor in 1939

Mahler Symphony No. 9, Vienna Philharmonic, Walter

PADA Leo Koscielny plays Boccherini's 9th Cello Concerto

|

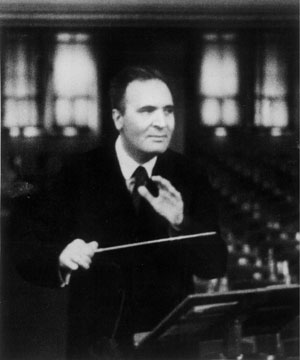

Bruno Walter's Mahler 9

The first recording - 11 minutes faster than his last

This week's new release

We return this week to the recordings of Bruno Walter - you will recall that a Bruckner 7 failed to make it into our catalogue recently thanks to the technicalities of copyright. No such problems exist here with the conductor's first recording of Mahler's 9th Symphony from January 1938. When I first looked at the timings of this recording I assumed there must have been some cuts made for the purposes of 78rpm recording, but no, it's all there. I lined it up against Walter's 1961 stereo recording (PASC376) and despite the earlier recording being some 11 minutes faster, all the notes appeared to be there in both.  | | Mahler |

All of which makes it rather difficult to decide what a "definitive" performance of this music should be like. After all, Walter, to whom the work is dedicated, performed its world première after the death of its composer, who never lived to hear it played. The two worked together for many years, and if there is one conductor who can be said to have known the mind of Mahler, surely it is Bruno Walter. I wonder if anyone timed the first performance, back in 1912? In all probability it was different again. The 1938 recording has been widely attributed to the concert of 16 January of that year. Certainly it is live. Yet, as Mark Obert-Thorn pointed out in his notes for the Naxos issue a few years ago, the matrix numbers, although consecutive, indicate that two of the sides are of earlier provenance than the rest. It seems most likely therefore that the concert of the previous evening was also recorded, and that these account for the errant matrix numbers on the 13th and 20th sides. The recording has long been regarded as one of HMV's better efforts of the 1930s, an era when great things were possible, but quality could also be rather hit and miss. Although "full frequency" recordings wouldn't officially be on the cards until the end of the imminent war, a number of recordings were being made in the late 1930s which easily transcended the expected upper frequency limits of commercial 78s of the day, and happily this is one of them.  | | Bruno Walter |

It must be admitted that it's not entirely successful at the top end, perhaps one reason why nobody was advertising wide frequency ranges until Decca's ffrr series some 7 years later. There's a tendency to high frequency distortion or blasting at some peaks, which I've worked hard to temper. Nevertheless there's a lot more for XR remastering to work on than is often the case from the late thirties, and the results are a revelation. I'll admit I've been sitting on this for nearly six months now; having begun the Walter Mahler series with his last recordings, including that slower 9th from 1961, it seemed wise to hold onto this for a while. Returning to it to put the finishing touches to it this month was once more a delight, both musically and technically - new updates to my favourite remastering software allowing me to work further on those distortion problems, resulting in an even better finished sound than I might have managed back in January. One of the joys of a digital subscription to Gramophone magazine is the ease of access to back issues, re-scanned more accurately than in their first, free online incarnation, and more accessible than before. In hunting down archive material whilst researching this week's recording, I came across a fascinating article by Fred Gaisberg, the architect of HMV and EMI, on the subject of Bruno Walter, which accompanied the first review of the 9th Symphony recording. I've reproduced quite a lot of it below, not only because I find it a wonderful insight into both conductor and recording impresario, not to mention the difficulties both faced in the light of events in Germany and elsewhere in Europe in 1938, but also for a single line which I've highlighted in bold below. Perhaps herein lies an answer to the question I raised above about authenticity and "definitive" performances?

| | Fred Gaisberg |

Bruno Walter - by Fred Gaisberg

WE have broken new ground in recording Bruno Walter with the Orchestra of the Conservatoire of Paris. In consequence of recent happenings in Austria, new associations have had to be formed. Bruno Walter is, it would seem, fated to be a storm centre, and the last five years in particular have been for him one long succession of dramatic episodes. He has come out with a clean sheet, and has at the same time succeeded in retaining the admiration and esteem of his colleagues in a rare manner. This latest recording took place in the very modern Salle de la Chimie. At first only slow progress was made, and after the session Bruno Walter apologised, saying: " You know, it is like a honeymoon, often-times things do not go so well. . . . Anyhow, the material " (meaning the instrumentalists) " is good. We'll make up for it to-morrow." Later on we discussed our last recording in Vienna, when on Sunday, January 16th, in the old Musikverein Hall, during an actual performance, we recorded the complete 9th Symphony of Mahler. These records (twenty in all) turned out extraordinarily successful, and Bruno Walter recalled that that was the last time, alter an association of more than twenty years, that he had waved the baton over that venerable orchestra for gramophone recording. It was the swan song of the old Philharmonic Orchestra (Gustav Mahler's own orchestra) and the performance was worthy of the occasion.  | | Walter in 1912 |

Bruno Walter as a young man was Gustav Mahler's first Kapellmeister at the Vienna Opera from 1901 to 1907 (when Mahler resigned and left Walter co-director with Franz Schalk). Thus he worked at the feet of his master, who studied with him all his compositions and discussed his aims and ambitions. Indeed, the 9th Symphony is dedicated to Walter, who, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, gave the first performance of it a year after Mahler's death.

Bruno Walter is a tireless worker. His day in Vienna often consisted of a rehearsal in the morning, recording in the afternoon, coaching or taking a vocal rehearsal at 6 p.m., and a performance at the Opera in the evening. On one occasion he actually fitted in a recording even after the opera, when it was pointed out to him that that was the only time the Singakademie was free! It seems that he is only happy when every spare moment of his time is occupied. Just before the "Anschluss" became an accomplished fact he told me how thoroughly happy he was. He had just signed a contract for a long term with the Vienna opera, and was beginning to do fine work. This last season all the performances were on a much higher level of excellence, due to his meticulous preparation of the operas. He prided himself on presenting a new "Aida," "Dalibor," "Orpheus'' and "Carmen." He was proud, too, of a new Roumanian dramatic tenor he had discovered and had just insisted on signing up for seven years. There is no doubt of his great capacity in the organising and arranging of an opera season, as shown by the results obtained at Covent Garden, at the State Opera in Berlin, at Salzburg, Vienna and elsewhere. In the recording room Bruno Walter impresses one with his practical and easy approach to his job. This belies somewhat the romantic emotion he puts into his conducting in his renderings of Mahler and Bruckner. He has said that he always tries to approach even the oldest and most hackneyed work as though it was a new composition which he was playing for the first time. The freedom of his relations with members of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra met with its reward in the unstinted support they gave him, which undoubtedly was very largely due to the fact that it is his habit to treat the members of an orchestra as colleagues and not merely as workers. When coaching an orchestra, he deprecates any appearance of teaching symphonic musicians how to count 1, 2, 3, knowing that this would not only bore them, but would offend the artist in them. Such perfect recording as that of Mozart's D minor Piano Concerto, in which Bruno Walter plays the solo piano part and also conducts, could hardly be obtained without this instinctive co-operation of the whole orchestra. These records, by the way, gave Bruno Walter extreme pleasure, and are amongst his greatest treasures.  He is very definite as to the value of recorded music, and says: "What would wenot give for records of Mozart, Chopin or Beethoven; even of Liszt and Brahms? We listen hungrily to verbal descriptions of their playing, told to us by people who yet know only from hearsay how they played. Recording is a great blessing, and the engineers have as great a responsibility to make it more and more real, and to see that the recording of works of great musical geniuses is not neglected." During a pause in recording, Bruno Walter recalled some of his early experiences, a few of which I reproduce hereunder with some little amplification of detail. Born in Berlin on September 15th, 1876, he was also educated there. His early masters were Hans von Bülow and Gustav Mahler. He knew Arthur Nikisch and held the highest esteem for him. It was one of his regrets, he told me, that he never met Bruckner personally. All his knowledge of that great composer was gained from Mahler, who knew him intimately. For many years Walter tried to get closer to Bruckner, but was never successful in doing so, and says that only in the last ten years has he understood him, and now he could not live without him. Bruno Walter has great faith in the enduring qualities of the music of both Bruckner and Mahler for the reason that, to use his own words, "it is music that goes to the depths of a man's soul." No young musician ever had such opportunities or such a master. During some seven years Mahler delegated to young Walter a large share of his duties, discussed with him his compositions, and sought his advice. The confidence engendered by these solid seven years of study and experience is the secret of Walter's perfect master-touch. He never distorts his music for the sake of "gallery effects."... ...Quite recently Bruno Walter, to his great joy, has been presented with full citizenship by the French Government. In his new capacity he has been invited to take charge of the French Music Festival to be held in Paris, Versailles and Fontainebleau in the spring of 1939. The French Minister of Fine Arts has made it clear to the Doctor that he is to engage the finest artistes and no means are to be spared to make the Season the best ever. It is even suggested that possibly Toscanini himself will be associated with Dr. Walter in this Festival... The Gramophone, January 1939 (excerpts) Andrew Rose

14 June 2013

|

|

Bruno Walter's world première recording of Mahler's 9th Symphony

"I would urge everyone who cares about Mahler to listen to it" - Gramophone

MAHLER

Symphony No. 9

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

Bruno Walter conductor

Recorded 1938

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer:

Andrew Rose

Web page: PASC 389 Short Notes

None brings one closer to its world of feeling or takes one more deeply into its spirit. Its fires are white-hot and there is a blazing intensity that in my experience has never been surpassed on the gramophone. There is a demonic passion to the Rondo Burlesque (the orchestra play as if their corporate life is at stake) and the final Adagio has a poignancy that once heard is not easily forgotten. I would urge everyone who cares about Mahler to listen to it. - Gramophone

Some 26 years after he'd conducted the world première with the same orchestra, and shortly before being obliged to leave Austria, Bruno Walter in 1938 conducted the work Mahler had dedicated to him, his 9th Symphony, in concerts recorded in Vienna by HMV. It's a blistering performance, some 11 minutes faster than his 1961 CBS studio recording. And in this new XR remastering it sounds absolutely astounding - for any recording of this era. A full frequency response, amazing dynamics, and the full sweep of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra come together in a truly magnificent release.

Notes On this recording Bruno Walter's historic first recording of Mahler's 9th Symphony, which he takes some eleven minutes faster than his 1961 Columbia recording (PASC376) has long been regarded as one of the great artefacts of the history of music recordings. It was remarkably well-made for its day, and here, after extensive XR remastering work, is revealed to have held within the grooves a quality of sound that is quite incredible for any 1930s recording. Despite some occasional upper end distortion, this is a full frequency recording, and it sounds magnificent as a result. Andrew Rose Review EMI CD reissue 1989

Bruno Walter conducted the first performance of Mahler's Ninth Symphony in 1912 (it is dedicated to him) as well as this, its first commercial recording. It bestrode no fewer than ten 78 rpm discs and consumed many fibre needles! (I recall paying five shillings or 25p a record for this secondhand-and playing the set almost every evening for weeks on end, doubtless to the despair of those within earshot.) Although later performances (including Walter's subsequent CBS recording in the early 1960s) have offered more polished orchestral playing and more vivid recording, none brings one closer to its world of feeling or takes one more deeply into its spirit. Its fires are white-hot and there is a blazing intensity that in my experience has never been surpassed on the gramophone. There is a demonic passion to the Rondo Burlesque (the orchestra play as if their corporate life is at stake) and the final Adagio has a poignancy that once heard is not easily forgotten. Even younger readers unencumbered by nostalgia will, i think, recognize the authenticity of feeling here, and I would urge everyone who cares about Mahler to listen to it.

Of course, there can be no such thing as a 'definitive' performance but this is as near as one can get. This and a modern recording such as the Karajan (DG) or the Bernstein (CBS) are all one needs. Some years ago the Walter was excellently transferred to LP by Anthony Griffith (World Records-nla) with the Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony and the Siegfried Idyll as a fill-up. Let us hope that room can be found for the former as a fill-up, say, to Walter's 1936 set of Das Lied with Kerstin Thorbord and Charles Kullmann, which must surely follow before too long. The digital remastering by Keith Hardwick enables one to hear more detail than before. As AB's note says, "more then 50 years later it [the Mahler Ninth] still carries a unique charge in terms of dedication and intensity of utterance".

R.L., Gramophone, August 1989

Review HMV 78rpm release, 1939

This, I understand, is a limited issue, which will be prized by those who love the composer's music, not only for its own sake, but because of the associations of Walter and Vienna. The admirable recording was made at a concert a year ago. The conductor has written of Mahler with persuasive affection, and here is his testament of interpretation about a work that cannot be heard without deep sympathy for a composer who did not live to hear it. If he had, it seems likely that he might have compressed parts of it. It cannot be denied that extreme length is apt to deter well-wishers ; but it may be more rewarding, in the end, than acerbic brevities in which the heart pulsates too feebly, and the rhythm too brashly: a pulsation oddly paralleled, one notes, in the cock-a-whoops of the petty, who cannot uphold their idols without spitting upon those who do not share their adolescent enthusiasms: the surest sign, this, of the true shamateur, There is room for every kind of real devotion, whose deepest proof is often the quietness of the devotee, but I have no use for the mere fandom of the half-baked, One may well wish enthusiasms to be shared (though, as a medical writer on the late "slashings" pointed out, the followers of evil, just as much as the devotees of righteousness, are urgent to make converts) ; but I think the great bulk of intelligent music-Iovers now realise (even if other would-be dictators do not) the silly futility of attempted conversion by the bludgeon.

We listen, then, with all possible sympathy to these distinguished records of music that came at the end of a life too soon cut off (Mahler was little over fifty when he died in 1911). His belief in devotion to spiritual intimations was well expressed in his saying "One docs not compose: one is composed." E. N. has aptly said "Mahler's is the last noble mind in German music," He sings, in the Song of the Earth, his twilight song. In the ninth symphony, which came after, the feeling is perhaps more equally divided between personal resignation and our sense of the end of German romanticism. Strauss, in some measure, had similarly sung, but in Mahler is a spirit of finer texture : one might say of it at its best, of divination. Heard against the background of historical knowledge, and with some appreciation of the forces that we now clearly see were piling up in those so deceptive years of the first decade of the century ; heard, too, with some understanding of the Austrian scene, of Mahler's desire to escape from his long toil in the opera-housc, such music has much to say to the inseeing and inhearing. The quieter moods of the first movement are so quickly broken by dramatic urgencies ; here is obviously a powerful drive of interplaying forces ; superficially the most immediate reference is to the Strauss tone-poem style, but no "programme" is given us. We shall probably regard the music as a mentally concentratcd (if physically extended) working-out of problems not new, but now seen more clearly and more sharply suggested to the listener.

The second movement (beginning at side 8) turns again to the simplicities of old German and Austrian life, by making use of the style of the country dance, the Ländler ; but tills is no happy motion of minds at rest and bodies glad to keep them so. Not only the very striking orchestration (that throughout makes the music so vivid, even if sometimes almost affrighting), but the abrupt, perhaps harsh-feeling ejaculations bring a sense of doubt, which some might interpret as bearing a heart of sadness, expressed in a brusque heaviness. Though one does not at all attempt a comparison of values, it comes to my mind that here is some tincture of thinking-into-the-future, as well as of the past, not unlike (yet on a different plane to) that which late-Beethoven injects into an otherwise pcaccful world-and, so doing, makes it uneasy, dangerous, foreboding. We should not read too much, where so little was given out ; but the music does seem full of strange finger-posts, an impression not lessened by repetition.

The third movement (side 13), called "Burleskc," adopts a more open wildness and stronger contrasts, and develops the contrapuntal art that Mahler so greatly esteemed (Bach and Beethoven were his prime delights). The word " bitter " is much in one's mind ; but it is not easy to define the nature of the music, as its so varying lights sweep the sky of the mind of composer and listener. One searchlight may pick out an object for A, whilst another light momentarily blinds B. A cloud, even, may seem like a bomber.

Finale (side 16). It is in moments such as the beginning of this movement that the faith of some who may have wavered about Mahler should be deepened. That does not at all mean that I think one ought to cherish equally everything written by a man who can write greatly ; I am all for making distinctions ; and the strongest of them all is, I think, not made for us, but by us: to adapt Mahler's phrase that I quoted, about composition, we do not, in the end, distinguish, we are distinguished (however undistinguished, in one sense) : nature, temperament, upbringing, determine our bent: and so, perhaps, the less we deave others about that the better. But however we choose to regard late Mahler-whether as chiefly a testimony of unrest, uncertainty, self-doubt, as a more important future-forecasting than some of our friends consider it, or even as a too poignantly coloured decadence of romance, I cannot think that so remarkable a revelation of the man's spirit at the end of his life can fail to impress any musical mind and move any open heart.

W.R.A., The Gramophone, January 1939

|

Leo Koscielny plays Boccherini

| | Luigi Boccherini |

PADA Exclusives

Streamed MP3s you can also download

BOCCHERINI

Cello Concerto No. 9 in B flat, G.482

Leo Koscielny cello

Munich Radio Orchestra

Hans Rosbaud conductor

Recorded c.1950

Issued as Vox PL6560

This transfer by Dr. John Duffy

Over 500 PADA Exclusives recordings are available for high-quality streamed listening and free 224kbps MP3 download to all subscribers. PADA Exclusives are not available on CD and are additional to our main catalogue.  Subscriptions start from €1 per week for PADA Exclusives only listening and download access. A full subscription to PADA Premium gets you all this plus unlimited streamed listening access to all Pristine Classical recordings for just €10 per month, with a free 1 week introductory trial. Subscriptions start from €1 per week for PADA Exclusives only listening and download access. A full subscription to PADA Premium gets you all this plus unlimited streamed listening access to all Pristine Classical recordings for just €10 per month, with a free 1 week introductory trial.

|

|