HALF PRICE FLACs

|

| |

All FLACs of this release 50% off for one week only

CANTELLI

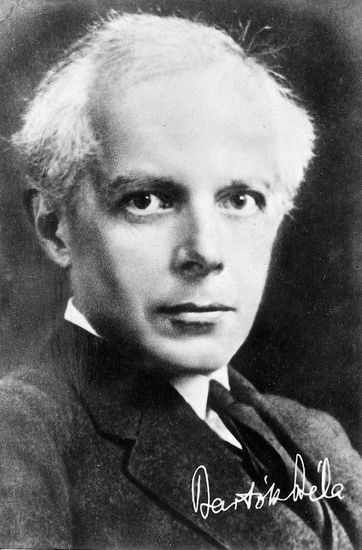

Conducts Bartók

Music for Strings, Percussion & Celesta

Boston SO, 1954

Concerto for Orchestra

NBC SO, 1949

CLASSIC REVIEW

In these days of slick CDs sounding as if they were recorded nowhere at all it takes a lot to get a cynical old beast like me excited. However this Pristine Audio Bartók release was thrilling from the first hearing.

Okay, Guido Cantelli (1920-1956) was so very special and his death in a plane crash in Paris robbed the world of a genius but he could be a bit wayward now and then. I cite his Britten 'Sinfonia da Requiem' which he excavates with his orchestral instincts but at the expense of what Britten actually wrote. It is in fact the only serious lapse I can recall. Damned exciting though and Britten agreed.

If you haven't heard his Brahms, Schumann and Tchaikovsky you haven't lived. Cantelli was the assoluto of the orchestra with a commanding ability to draw evident pleasure from musicians from many nations. His accuracy of tempo was greatly admired by men far older than he.

The Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1937) is a very tough work to deliver successfully. Cantelli's 1954 recording reminded me of the first time I heard Pierre Boulez do it as the new conductor of the BBCSO in his first Prom season in the Royal Albert Hall, London. Boulez eschews the baton and the stunning sound was as if his fingers were pulling invisible strings to all players; the enormous audience was silent. In all probability there was no greater silence than in this Cantelli live performance of 1954. That thrill of Boulez was brought back by this astonishing release. If anything, Cantelli is a nose ahead because Boulez never replicated that live thrill on record. We are fortunate that Cantelli was recorded live on 27 March 1954 . I wonder if the WGBH-FM Boston engineers on that night knew that they were broadcasting perfection. It seems likely that members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra knew that something special was happening.

What is special is that this complex work with dynamic extremes opens with the strings muted in violins and violas then goes to the rest of the strings at a measured pace; shades of Vaughan Williams 6th Epilogue of later years. The added strings, under masterly discipline, build up the keening dynamics to a climactic point. It is as if the entry of the timpani is required to return the strings to their wandering quest with a little goodbye from the celesta.

Cantelli takes the second movement Allegro at score pace with just a few valid Magyar syncopation strokes. He makes it fun after the rather pessimistic opening movement and there's brilliant attention to pizzicato to set against the celesta interventions. It all makes sense with celebration coming like the resolution of a lovers' spat.

The Adagio third movement is slightly quicker than Boulez and Solti on record but my "reference" favourite old EMI LP with Gyorgy Lehel conducting Hungarian musicians is just a fraction over Cantelli's 6:12.

That touch of urgency after the slow opening of wood blocks and timps followed by lower strings is a masterstroke. Cantelli's pace makes sense when the sliding string passage against celesta and pedal timp moves to resolution and development. Most conductors miss the point that if Bartók had wanted a peak in the violas he would have written it. Here we find Cantelli getting the best of the lower strings and varied percussion (including piano) at a slower pace than even Lehel. The tensions of stretched harmonies flow out uniquely in my experience. Cantelli even keeps the stronger string dynamics without vibrato. The result is to weld this strange music to the musical agenda of the whole work if one listens hard.

The final movement, Allegro molto sounds as if a Magyar was conducting but the score is clear. The difference between Lehel and Cantelli is a cigarette paper except for phrasing points when the fun music needs to romp. Cantelli is maybe a bit less abandoned than Lehel but remarkable nonetheless.

The biggest danger with this work is that the movements can seem disparate. I feel that about the Solti (Decca), which is probably the most familiar. Boulez knits it well enough in his recordings but he was better live. Lehel's authenticity is frankly outclassed by Cantelli's depth of understanding of the actual music.

The Concerto for Orchestra (1943) is from Bartók's very few American years when he left Hungary to avoid Nazi oppression. That period saw his last quartet - one of profound sadness - and a few interesting works. However for him there was no red carpet treatment and he was already in poor health with the leukaemia which caused his death in 1945.

Koussevitsky commissioned the Concerto for the Boston SO but the Cantelli version is with the NBCSO and was recorded for/from radio on 29 January 1949.

The invention of a true 'concerto for orchestra' in five movements was brilliant enough in itself. In it Bartók gave value aplenty by looking back to Europe and his beloved Hungary with unusually generous orchestration. Even so, there was more. Bartók never learnt English - even the American version - but was well aware of events during a terrible war. As well as retaining his sense of humour sufficient to satirise Shostakovich's 'Leningrad Symphony' in the fourth movement he knew that his fellow composer was under a dictator just the same as his own country was by invasion.

To my mind Cantelli in 1949 captured the essence of the Concerto as a supreme musician better than Koussevitsky, Reiner, Solti and even modern conductors such as Rahbari on Naxos. That said it's still difficult to say precisely how he did this; only listening makes the point. The faithfulness, discipline and genius of Cantelli is mercifully retained through this recording but just how Pristine Audio's engineers dig out the actual sonics as they do is a mystery to me.

Cantelli's analytical style with innate musicality makes sense of this as a concerto for an orchestra. Contrast this with a performance that communicates the work as 'a piece for orchestra in five movements' as it sometimes seems to be on disc. Cantelli spots exactly what Bartók intended in emphasis of orchestral sections. So did Reiner with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for RCA. The sound is better in this Pristine Audio release of tapes taken down before stereo.

Now the gripes. Only one of them is to do with Cantelli's performance. At the opening of the final movement there is a 12 note brass fanfare but Cantelli delays the last one for longer than the score shows; it sounds a bit odd - especially for Cantelli. If this is due to editing I trust that Pristine Audio's genius engineer Andrew Rose will let us know. With the remainder of that movement simply so perfect I am probably being picky. However with the rest of this performance so perfect a 'glitch' like this stands out.

My other gripe is that the review copy I received was in a little wallet with front and back sheets usually to be found in a jewel case. There's no insert and no information about the venues of the recordings. We can assume that the Boston Symphony Orchestra played in Boston Symphony Hall but I have no idea about where the NBC Symphony Orchestra was recorded. When a release is as important as this one the more information we have the better (Pristine offers recordings as downloads. This CDR was specially supplied for review so did not carry full documentation. Downloads are available from the Pristine website - Ed.).

Without reservation I recommend this issue. It's the closest to analogue sound by a genius that you will hear. That said, a good outboard DAC is essential, avoid headphones and use very good speakers. Then you will hear Bartók in extremely important works as near to reality under a conductor of genius.

If you like Bartók's music or are just getting to know it then you must have this CD. It's the very reference model of the works in sound so close to real that it's truly amazing. Simply essential.

Stephen Hall

MusicWeb International

Recording of the Month October 2007

ALL FLAC DOWNLOADS OF THIS RELEASE ARE HALF PRICE FOR ONE WEEK: PASC 081

NB. Offer does not apply to CDs or MP3 downloads

|

PRESS COMMENT

| The Rest Is Noise

BLOG EXCERPT

27 May 2013

by Alex Ross (Music Critic, The New Yorker)

"We're being bombarded by reissues of Rite recordings: Decca has released a twenty-disc box set, and Sony has remastered Bernstein's feisty NY Phil version, with extremely detailed notes by Jonathan Cott. I'd like to draw attention to Pristine Classical's superb new transfer of Stravinsky's own 1929 account, with the Walther Straram orchestra. As Richard Taruskin has pointed out in his centenary lecture, modern renditions of the Rite, vivacious and showily perfect, have robbed the work of some of its ominous energy; this recording, while full of mistakes and messy moments, has a raw, spooky power all its own. Back on the Wagner front, Pristine has done wonders for Furtwängler's La Scala Ring."

| |

|

|

CONTENTS

| |

This Week Bartók replaces Bruckner

Replay Comparing cartridges for XR remastering use

Anda plays Bartók's three piano concertos

PADA Szigeti and Schnabel play more Beethoven

|

Comparing record replay equipment

How can an Ł80 cartridge sound better than an Ł800 cartridge?

This week - Bartók, not Bruckner

| | Béla Bartók |

For the past two weeks I've been promising you Bruno Walter's superb 1961 stereo recording of Bruckner's 7th Symphony. Today I'm afraid I have to announce that it's unlikely ever to see the light on the Pristine Audio label, wonderful as our long-ready remastering sounds. It's fallen victim to an assumption I made when I began working on the remastering and should have checked first: despite being recorded during Bruno Walter's quite amazing late burst of studio activity with Columbia at the end of his life, it was held back by the record company until 1963. Had I first sought out the Gramophone review of this particular release I would have known to be more careful - the opening line, published in December 1963, runs thus: "SO the sheaves still continue to come in from the late harvest of Bruno Walter's career - Bruckner, Wagner, Mozart, Brahms and Mahler this month, a store to be grateful for indeed..." I'd better be more careful in future - because although there's always the chance that a record such as saw release in the USA before reaching the UK's shores (and thus the attentions of Gramophone's reviewers), it's quite likely that a good number of other recordings from this late period in the conductors life remain in copyright in Europe, and thus beyond our reach. As I've written here before, there remains the outside chance that Europe's collective national governments might not all get around to ratifying changes to our copyright law (to bring it into line with what the ever-dwindling number of global mega-record-companies want in order to preserve Beatles royalties and the like), but I hold out very little hope. So my apologies both to the reader of this newsletter who suggested it, and to everyone else who was looking forward to hearing it this week. Instead we bring you the three piano concertos of Béla Bartók in classic performances by Geza Anda with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra under Ferenc Fricsay, a conductor who's absence from our catalogue has been noted by a number of correspondents.

The recordings, which were made in a Berlin church in the two years before the Wall went up by DGG, were technically well made, but one senses that in their eagerness to ensure a clear sound from the soloist led them to curtail the very reason so many recordings have been made in that particular location, as Variety once pointed out: "The Jesus-Christus-Kirche was a favorite recording venue of von Karajan's, having been discovered by his predecessor, Wilhelm Furtwaengler, and is famed for its extraordinary acoustics." Recording engineers often find themselves battling against the "extraordinary acoustics" of a room, erecting baffles and non-reflective temporary walls to try and isolate the sounds they seek to capture. Coupled with close-microphone techniques these can reduce significantly the appearance of natural reverberation, something the Bartók recordings rather lacked. Reinstating a little of this, coupled with some tonal corrections and pitch stabilisation (particularly at an edit point in the Third Concerto), produces a truly magnificent sound, as I'm sure you'll agree if you care to listen to this week's sample. It's not Bruckner, I'm afraid, but it is pretty fabulous if Bartók is your thing - and coming to these recordings with little knowledge of the pieces concerned, I must admit to being particularly struck by all three of them! Playing with needles

A few weeks ago I was e-mailed by one of our customers here in Europe. He began in what at first appeared a rather curious manner: "I don't know whether I should love you or hate you. For years I have searched for classical and opera music and was rather proud of what I have collected. Now that I have listened to the previews of your restorations I know that have to ditch quite a bit if I want first quality..." As you can see, things rapidly improved after the first sentence! He went on to make me an offer on a cartridge: "I was a technical translator for a Swiss company that specializes in precision diamond grinding and they sold me one at cost. I no longer own any LPs but still have the pickup which I would be glad to donate it to someone who has any use for it. I don't know the exact model, but it was built in the 1980s and it has seen little wear..." I suggested he send it to me at his convenience - although I'd complete faith in my two Benz Micro Glider cartridges, each custom-tipped for me by Expert Stylus in England (one for stereo and one slightly wider for mono LPs), my interest was piqued by the title of the original e-mail, "Van Den Hul cartridge".  | | Fidelity Research FR1 |

On Saturday a package arrived, containing one cartridge, firmly installed in a headshell, leaving some of the writing on it hidden away. When I unscrewed the cartridge from the headshell I discovered that it was not in fact a Van Den Hul but instead a Fidelity Research FR1 Mk.3. I had no idea what this was, but got to work on some research (how did we ever manage before Google and the Internet?). It turns out that Fidelity Research was a Japanese hi-fi company, best known it seems for their moving coil cartridges. Whether they continued beyond the 1980s I don't know, but their roots appear to lie in the 1960s, and they were quite highly regarded at the time. It turns out the original reference to Van Den Hul came with the retipping of the stylus (and possibly other rebuilding work on the cartridge that's been lost in the mists of time...). After installing the cartridge I began transcribing some chamber music recordings from the 1950s and was immediately impressed by the sound I heard. I got to work again on the search engines and Gramophone's impressive online archive (at Exact Editions, for subscribers only I'm afraid). Here I discovered a review of the Mk2 from September 1977, and adverts from the late 1970s which included both the Mk2 and Mk3 side by side - the retail price of the latter in late 1978 being around Ł79. I also discovered elsewhere that the Mk3 was supposedly the first moving coil cartridge ever to use silver wire in its coil. Now back in 1978 I was celebrating my 10th birthday and listening to Blondie and Abba. I had little concept of hi-fi, and no recollection of how this kind of thing was regarded among the hi-fi buffs of the day. I suspect this puts me at a disadvantage among a number of readers here - but it does mean that I can appraise the cartridge without prejudice. I can also approach it in a different way to most:  | | Benz Micro Glider |

After transcribing a selection of music with the FR1 I switched back to my modern Benz cartridge, which currently retails for Ł795. I then set about doing what I would normally be doing with any recording I transcribe: remastering it. I'm less interested in the direct sound of the cartridge than I am in how its output will sound once I've put it through the XR remastering process, as this is what will be its ultimate test. XR re-equalisation might fix a tonal problem inherent in a source, but it can also be very revealing of any faults. So, being careful to apply the same treatment to transcriptions from both sources I lined them up, side-by-side, on my digital multitrack, allowing me to switch with the click of a mouse between the two 32-bit recordings as the same notes played simultaneously on two parallel tracks. At this point I became slightly confused as to which track was which - was track one the Benz or the Fidelity Research? - and this seemed not a bad confusion to maintain whilst listening, first on my studio monitors, then on my very revealing Sennheiser headphones. Both sounded great, but there was a clear difference. One had a rather dry, clinical sound, slightly austere, where the other seemed to offer a warmer picture, with a sense of space and air around instruments that sounded more alive. I don't like trying to quantify differences in sound like this, but I knew from what I was hearing as I switched between the two unmarked sources which appealed to me more. So I returned to the master files I was comparing, and discovered that the slightly flat-sounding transfer was in fact my beloved Benz, and the sound I preferred (of the Fischer - Schneiderhan - Mainardi trio) was the older, Fidelity Research cartridge. I've read a number of theories since doing this test about the changes in cartridge design and tonal aspirations since the 1980s - suggestions that cartridge designers felt the need to emulate CD sound and detail and ended up with a "sterile, cold-sounding" product, for example. But whatever the reason for this, I felt that, for the kind of recordings I work with, and for the way that I work, the FR1 had the edge. I'm not a "normal" listener, and it may also be the case that the Benz sounds better before I get my remastering hands on its output, but for the time being I'm switching sides to the Fidelity Research for my stereo LP work (and those mono LPs pressed in the stereo era to stereo groove widths) - of which I suspect you'll be hearing quite a lot over coming weeks. Today's Bartók is the first fruit from this change - as much as it would have sounded wonderful had I transcribed it using my Benz cartridge, I like to hope it has an extra edge, barely discernible on any but the finest hi-fi systems, thanks to the FR1 Mk3. As I type this I'm now listening to the Hollywood Quartet playing Dvorák, also recently transcribed and in the process of being remastered, and it sounds pretty fabulous too! Andrew Rose

31 May 2013

|

|

Three of the greatest recordings of Bartók's Piano Concertos in new XR remasters

"A performance remarkable for its precision of ensemble, clarity and exactness of detail" - Gramophone

BARTÓK

The Piano Concertos

Geza Anda

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra

Ferenc Fricsay

Recorded 1959 & 1960, stereo

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer:

Andrew Rose

Web page: PASC 388 Short Notes

Soloist and orchestra co-operate in exemplary fashion in a performance remarkable for its precision of ensemble, clarity and exactness of detail: Geza Anda in particular is to be congratulated for the way he romps through all the difficulties. The recording is excellent, the stereo even better than the mono. - Gramophone

More than half a century later Geza Anda's interpretations of the three Bartók piano concertos, recorded with fellow Hungarian, conductor Ferenc Fricsay, in Berlin for Deutsche Grammophon remain at the very top of many people's best of lists.

Bringing power, technical brilliance, and a deep and fundamental understanding of the music to bear, these are unbeatable interpretations. Now they can be heard in a sound quality that's quite astonishing, with a vibrance, clarity and body that the 1959 and 1960 stereo recordings lacked, in these new XR remasters from Pristine.

Notes On this recording These recordings, drawn from a later DGG pressing which brought together Bartók's three piano concertos and the Piano Rhapsody in a 1970s double-LP, are still prized more than fifty years later as among the very finest interpretations of these works. Brilliant performances were captured very well in fine stereo by Deutsche Grammophon's engineers in the Jesus Christus-Kirche in Berlin.

As has previously been the case with the finest recordings of this era, I had to be certain there was more to be brought out of these recordings through XR remastering before committing fully to this project. A series of extensive transfer and listening tests convinced me that, indeed, there was. Careful pitch stabilisation has helped reduce or eliminate wow, flutter, pitch drift and a noticeable edit in the Third Concerto where the pitch drops from one take to the other. The overall sound is now fuller, richer and clearer, with a hint of the musically-sypatheric acoustic properties of Birmingham Symphony Hall filling out the rather artificially-dry original sound to great effect. Andrew Rose Review Concertos 2 & 3

At very long last we have a worthy recording of the Bartók Second Concerto, a work whose previous interpreters (including the admirable Andor Foldes, whose performance received Bartók's own blessing) have all suffered from recording qualities ranging from indifferent to abysmal. This will be valuable in helping to spread a knowledge of an important work in Bartók's output which is rarely heard in the concert hall, probably because of the ferocious difficulty of the solo part - Bartók seems to have had in mind huge hands with permanent built-in octave and thirds mechanisms. The music does not deserve this neglect, and though it is "tougher" in idiom than the more mellow Third Concerto it has in fact had a consistently successful reception ever since its first performance (by the composer) in 1933. A bravura, lithe work, it abounds in motor energy and in contrapuntal vigour and resource (much of the material of the first movement - which is played entirely without the strings - reappears in inversion, or even in retrograde inversion, in the finale): the central part of the Adagio is a brilliantly fantastic delicate scherzo which looks forward to the Sonata for two pianos and percussion. Soloist and orchestra co-operate in exemplary fashion in a performance remarkable for its precision of ensemble, clarity and exactness of detail: Geza Anda in particular is to be congratulated for the way he romps through all the difficulties. The recording is excellent, the stereo even better than the mono.

There is no lack of recordings of the more popular Third Concerto, but the new one is, to my mind, way ahead of the field. Katchen's suffers from a lukewarm and lack-lustre finale; Haas's from a rather veiled recording; Fischer's (a good one) from a balance excessively favouring the piano, and from what I still feel is over-much rubato in the first movement; Sandor's from a rushed first movement, and over-reverberant recording and some muddy piano passages. Here there is a true balance between piano and orchestra and the performance is mostly very good indeed, with a particularly buoyant fugato in the finale . The ensemble has one lapse - the unison wind passage at figure 76 drags behind a little; and I personally don't care for Anda's rather mannered delivery of the opening subject both at the beginning and at the recapitulation; but otherwise this is entirely recommendable.

L.S., The Gramophone, May 1961

|

Szigeti and Schnabel play Beethoven

| | Artur Schnabel |

PADA Exclusives

Streamed MP3s you can also download

BEETHOVEN

Violin Sonata No. 10 in G, Op. 96

Joseph Szigeti violin

Artur Schnabel piano

Recorded 4 April 1948 in concert at the Frick Museum, New York City

This transfer by Dr. John Duffy

Additional remastering by Andrew Rose

| Joseph Szigeti

|

Over 500 PADA Exclusives recordings are available for high-quality streamed listening and free 224kbps MP3 download to all subscribers. PADA Exclusives are not available on CD and are additional to our main catalogue.  Subscriptions start from €1 per week for PADA Exclusives only listening and download access. A full subscription to PADA Premium gets you all this plus unlimited streamed listening access to all Pristine Classical recordings for just €10 per month, with a free 1 week introductory trial. Subscriptions start from €1 per week for PADA Exclusives only listening and download access. A full subscription to PADA Premium gets you all this plus unlimited streamed listening access to all Pristine Classical recordings for just €10 per month, with a free 1 week introductory trial.

|

|