|

The reeducation

Riding the horse, the immediate feeling was an intense lateral flexion of the spine concave to the right and a very pronounced transversal rotation shifting the dorsal spinous processes and therefore the rider's seat, to the right. In 1999, Jean Marie Denoix demonstrated that lateral bending of the equine spine was always associated with a movement of transversal rotation. "In the cervical and thoracic vertebral column, rotation is always coupled with lateroflexion and vice versa." (Jean Marie Denoix, 1999).

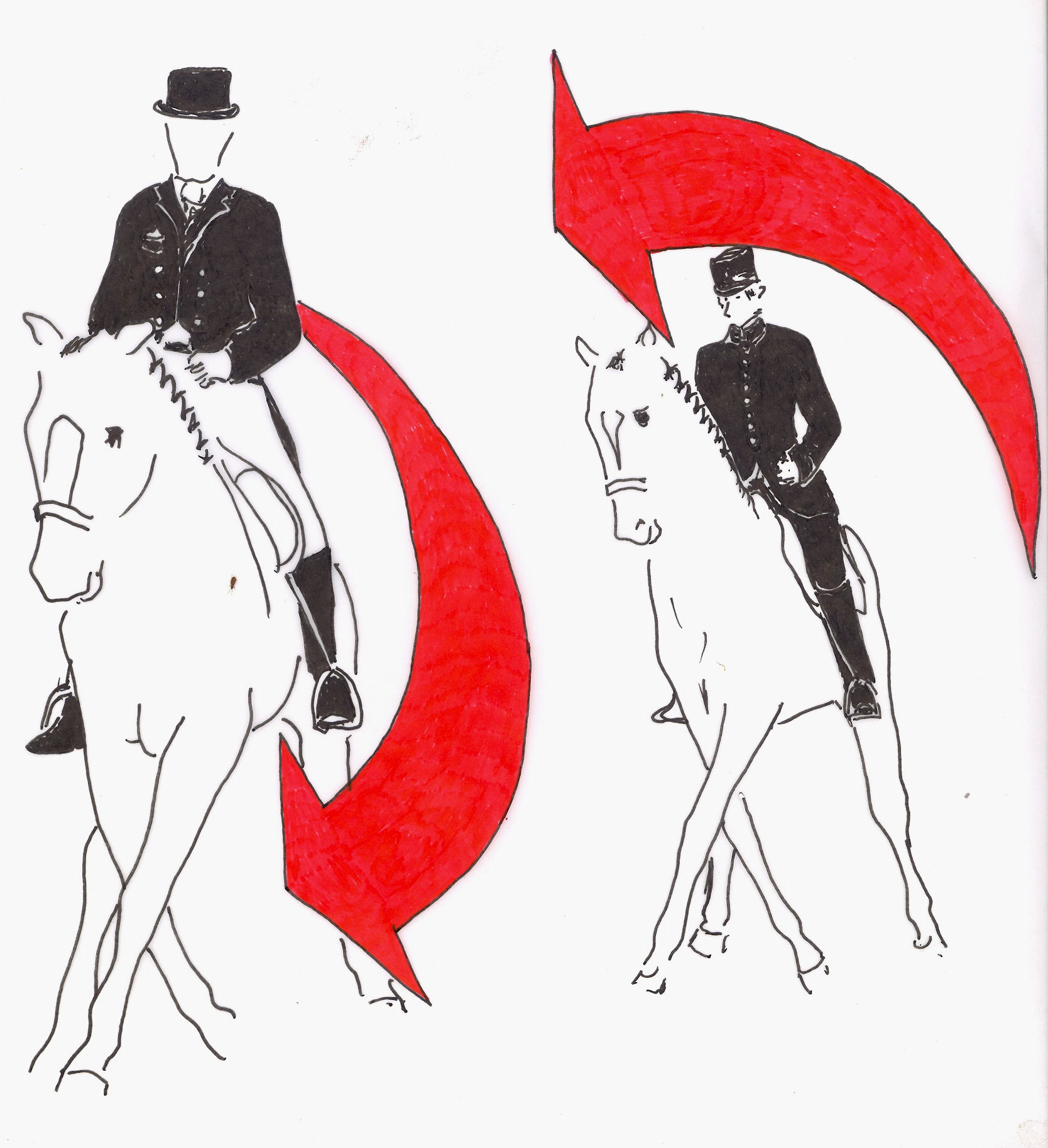

The best way to understand the concept of transversal rotation may be to observe what proper and inverted rotations look like. The horse situated on the right side of the picture executes half pass combining the proper arrangement between lateral bending and transversal rotation.

The horse situated on the left side of the diagram executes half pass combining lateral bending and inverted rotation.

For the same lateral bending, two rotations are possible. One is correct and therefore physiologically efficient. The other is referred to as "inverted" and therefore dysfunctional. When the spine is bended laterally to the right, proper rotation is a rotation shifting the dorsal spinous processes to the right. Doing so, the ventral part of the vertebral bodies is facing left. The rotation is then named left rotation since the scientific world labels the rotation in respect of the direction faced by the ventral part of the vertebral bodies.

In 1999,Professor Jean Marie Denoix DVM PhD, used his drawing skill to illustrate the phenomenon of transversal rotation. This diagram is inspired by Jean Marie Denoix's work.

Adding our own signature, we placed the thoracolumbar spine of a horse in the posture illustrated by Dr. Denoix. The segment of the spine illustrated in the following picture is highlighted here.

The view is from the front. The combination between lateral bending and transversal rotation is correct.

This type of rotation is referred to as left rotation because the ventral part of the vertebral bodies is facing left. The good formula is therefore right lateral bending and left rotation.

It is unfortunate that the scientific world elected to name the rotation from the direction faced by the ventral part of the vertebral body. The rider is seated on the top of the dorsal spinous processes. Therefore, when the dorsal spninous processes are shifting to the right and the rider is feeling a right rotation, the move is officially defined as left rotation.

For the same right lateral bending, "contrary" or "inverted rotation" will shift the dorsal spinous processes to the left.

Inverted rotation is illustrated in this picture. We maintained the same lateral bending but rotated the vertebrae in the opposite direction.  Such inverted rotation is shifting the rider's seat to the outside of the bend. Simplistic judging standards attribute the problem to improper fitting of the saddle or uneven weight distribution of the rider. In fact since almost every horse commences his or her athletic career with some imbalance between right and left side of the back muscles, the rider's tendency to sit preferentially on one side is very often a rider's adaptation to the horse's back muscles' imbalance, which in turn, aggravates the horse's muscular imbalance. Analyzing and addressing the source of the horse's vertebral column dysfunction is definitively more efficient than re-stuffing one side of the saddle.  This type of rotation is named right rotation because the ventral part of the vertebral bodies is facing right. Inverted rotation creates strains and shearing forces on the vertebral structure. The effect of these shearing forces and abnormal strains are visible at all levels in the show ring. For example, as we are already referring to the half pass, the move can be analyzed in respect of the horse's ability to sustained proper or inverted rotation. Horses are commonly seen losing suspension, amplitude and candence during half pass. Instead of focusing on the horse's ability to cross the forelegs above the knees, judges should base their note on the horse's capability to sustain suspension, amplitude and cadence all the way through the diagonal on half pass. A horse executing half pass in inverted rotation will easily cross the front legs above the knees but will be unable to sustain suspension and amplitude and consequently cadence through the movement.

In terms of lateral flexion and transversal rotation, the vertebral column combination of the horse on the lameness video was correct. The horse was coupling right lateral bending and left rotation. The problem was the intensity of the rotation. Usually,inverted rotation shifts the rider's seat to the outside of the saddle. By contrast, proper rotation does not normally shift the rider's seat much to the inside. Due to the nature of the bend, proper rotation simply places the rider evenly on both seat bones. The fact can be observed comparing the picture of the equine spine illustrating right lateral bending and proper rotation (left rotation,) and the picture showing right lateral bending and inverted rotation (right rotation.)

As I was riding the horse, the torsion of the horse's spine was clearly shifting my seat to the inside while turning to the right suggesting excessive transversal rotation. In fact, the direction of the rotation remained the same when turning to the left. The horse's vertebral column was permanently bent to the right whenever I was asking the right turn or left turn. Most of the lateral shifts that you have observed at the level of the shoulders and at other instants at the level of the haunches were due to this phenomenon.

Thinking about the reasons that could lead the horse to keep the spine permanently bend in this direction, two observations that I made earlier watching the horse in the stall came to mind. I noticed that the right scapula was aligned differently than the left one and that the right elbow was unusually close to the ribs. It was not dramatic; it was just an observation of his morphology. With this thought in mind a working hypothesis started to take form. The inward rotation of the right elbow may have altered the backward movement of the right forelegs during locomotion. As the ribs became gradually wider behind the horse's shoulders, the inward rotation of the elbow was placing the right elbow in contact with the ribs as the front limb was moving backward. The horse's brain adjusted to the situation bending the spine laterally concave right. The logic of the move was probably that such bending would yield the ribs slightly toward the inside of the bend giving more room for the backward movement of the elbow. Perhaps the lateral bending was insufficient and the horse's brain figured out that increasing the transversal rotation would shift the ribs a little further.

The left picture illustrates a horse's skeleton in normal standing posture. The right picture shows the three year old horse's situation. Over time, the horse literally wrapped his body around his right elbow creating outward rotation of the front part of the scapula, inward rotation of the right elbow, right lateral bending of the thoracic spine, inward deviation and exaggerated rotation of the pelvis .

On this illustration, the difference between normal and crooked is not as obvious that on the pictures showing lateral bending and rotation of the vertebral column. For clarity on these pictures, lateral bending and tansversal rotations are exaggerated. In motion, the amplitude of the horse's vertebral column's movements are relatively limited. The amount of torsion showed on this picture is close to the reality.

Interractions between lateral bending and deviation of the pelvis are part of the daily life with the horse. Lateral bending of the equine spine is localized in the 16 first thoracic vertebrae. When the cranial thoracic vertebrae are laterally bended to the right, the pelvis is deviated to the right.

There is also an interaction between proper or inverted rotation and the rotation of the pelvis. When the spine combines right lateral bending and left rotation, the pelvis is transversally turned in the same direction that the vertebrae. The right side of the pelvis is lower and the left side is higher. In such a vertebral column combination it is the vertebral arrangement that permits full benefit of a gymnastic exercise such as shoulder-in.

By contrast, if right lateral bending is coupled with an inverted rotation, as shown on this picture, the pelvis is transversally turned in the opposite direction. The right side of the pelvis is higher and the left side is lower. Such lateral bending hampers the horse's ability to work efficiently on the shoulder-in as well as any lateral movement

Considering that the horse was crocked while traveling in straight line, the pelvis was oblique in relationship to the axe of motion. The right side of the pelvis and therefore the right hip was also lower and the left hip was higher. Such abnormalities altered inevitably the kinematics of the right and left hind leg.

For instance, if for clarity we limit our observation to the kinematics of the hocks, the backward position of the left side of the pelvis engenders early alighting of the left hind leg and consequently a situation referred to as "functional straight hock." "Functional straight leg may occur because the hoof contacts the ground too far back." (James R. Rooney, Biomechanics of Lameness in Horses) The situation creates a functional or dynamic equivalent to the conformation known as straight hock. Such conformation is prone to lesion between Mt3and T3

By contrast, the right hips is forward in relation to the axe of motion and lower, creating the situation of a right sickle hock. The lesions commonly associated with morphological or functional sickle hocks are between TC and T3.

The horse did not have lesions in the hock at the time of the veterinary inspection because he was young and had not been under heavy training. Hock and probably stifle lesions would have occurred sooner or later if he had continued to move and perform with the spine crooked. In fact, there were visible signs of strain in the stifle on the right side as well as muscle fatigue in the sacroiliac attachment and lumbar region.

Interactions between back muscle imbalance and consequently vertebral column crookedness and abnormal limbs kinematics are the basis of our approach. The science of motion takes a direction diametrically opposed to conventional views which see legs' issues as the root cause of back problems. Although, the school of thought is now evolving; in 1999, Kevin Hausller makes a drastic step forward from conventional thinking. "Limb disorders are often treated exclusively, without investigating possible structural and functional interactions between the spine, upper limb, and lower limb." (Kevin K, Haussler DVM, DC, PhD, Preface of the Veterinary Clinics of America, Equine Practice, Back Problems.)

The main reason the focus is on the legs is that riding principles do not permit to efficiently access and influence the biomechanical properties of the equine vertebral column. Principles such as driving the horse onto the bit and lowering of the neck have a very superficial and quite primitive effect on the vertebral linkage.

Any vertebral column dysfunction induces abnormal kinematics and perturbes dynamics of the hind and front legs. The first priority is to update training and riding principles to actual knowledge of the equine physiology. The second priority is to take conscience that creating a functional athlete is not about submitting the athlete to stereotypes. Infantile ideas such as the thought that the correctness of the rider's aids guaranties the accuracy of the horse's performance omit the fundamental facts. For an exactly similar vertebral column dysfunction, two horses might present different limbs' kinematics abnormalities. The reason is that a horse can use different set of muscles to execute exactly the same movement. For example, "A visually identical hind limb extension in late stance may be accomplished by only hip extensor torque, only knee extensor torque, or any combination of these." (A. J. van den Bogert, 1998)

In 1954, Linus Paulin, who won the Nobel Price in Chemistry wrote, "Progress is built on investigations, analysis of cause to effect, factual documentation of test hypothesis," a process that the author referred to as "the search for truth." When the aim is to create a functional athlete and consequently a horse performing at his fullest potential while remaining sound, the truth is the equine physiology. A problem appears and the research is about identifying the source. Hypotheses can be made and they have to be verified. Such intellectual work is very different from opinion. Unfounded opinions don't want to be verified because they could be proved to be wrong. The report presented here is the factual documentation of a working hypothesis which turned out to be right. There have been many other cases where the initial working hypothesis had to be adjusted or even abandoned in the face of evidence unveiled through verification.

To verify the thought that the spinal torsion was the root cause of the lameness I tried to bend the spine a little more to the right but did not succeed. I attempted then to bend the spine to the left, but, that did not succeed either. In fact, it was impossible to create any lateral movement of the thoracolumbar spine to the right, nor to the left. The thought that some neurological disorder could hamper any motion of the spine crossed my mind. The only direction that I had not yet explored was dorso-ventral. I tried then to create a longitudinal flexion of the spine.

Then, another set of problems surfaced. The horse had been lounged in side reins which, as one can expect, was for this particular horse, very uncomfortable. The horse had already learned to protect himself pushing heavily on the side reins and consequently on the bit. As soon as I asked for a slight flexion of the poll, the horse braced against the reins keeping his neck and back rigid. I felt sorry for the horse but the problem was to try to figure out what could cause such lameness and if it was impossible to create some vertebral column movement, there was no hope to eventually reeducate the horse. He was obviously thinking about protecting himself; he was resisting out of frustration but also without anger. I insisted. I placed the poll slightly to the right to reduce the horse's possibility of resistance. At the end of the long side of the arena, after several minutes of resistance, there were two or three steps when the horse flexed the spine longitudinally. Instantly the gait felt better. Many of you noticed these few strides, and as the horse's neck was turned to the right you understood that I was asking shoulder-in. The gymnastic of shoulder-in would have been beneficial and in fact was later used abundantly for the horse's reeducation, but at this time, the horse had no idea of what shoulder-in could be.

The longitudinal flexion of the horse's vertebral column was not the result of a slight flexion of the neck. The involvement of the neck was simply one of the necessary elements. The main suggestion was reducing the range of motion of my own vertebral column. The thought contradicts conventional views which emphasize relaxation of the rider's back. The concept of the rider's back oscillating freely in synchronization with the horse's vertebral column movements is based on a misconception. The horse's vertebral column does not move widely during locomotion. To the contrary, the range of movement of the horse's vertebral column is extremely limited. The large intensity and diversity of forces perceived by the rider in the saddle has been erroneously attributed to motions of the horse's vertebral column. In reality the maximum range of possible movement of the equine vertebral column in the dorso-ventral direction is less than two inches and a quarter.

In 1980, Leo B. Jefcott measured the possible range of movement of the horse's vertebral column. Cervical vertebrae and ribs were removed as well as main muscles and ligaments. Dorso-ventral movements were measured supporting the specimens at both extremities. The thoracolumbar spine was then pulled upward until maximum flexion and then downward until maximum extension. Xrays were taken measuring the space between the dorsal spinous processes during flexion and then during extension. Adding the measurements obtained between each vertebra, Jeffcott concluded, "The total range of movement in the dorso-ventral directions of the equine back was only 53.1mm under these experimental conditions." (Natural rigidity of the horse's backbone, 1980). (53.1mm is a little less than two inches and a quarter)

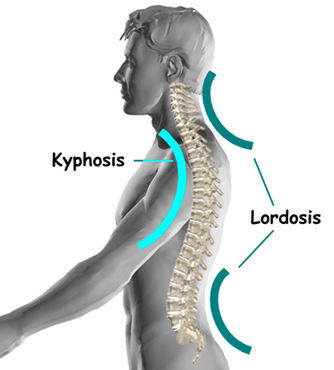

In the saddle, the rider is placed where the upward forces created by the hind and front legs meet. These forces induce movements of the rider's vertebral column. The situation is therefore a large amount of force that the rider's vertebral column needs to absorb within a range of motion that does not exceed the horse's vertebral column's range of motion. The most efficient way to achieve such control is to use the whole length of the rider's vertebral column.

One may think, why not use the maximum elasticity of the rider's lumbar region? That is a good question. The answer is that the horse's vertebral column cannot structurally move more than two inches and a quarter and that the main function of the back muscles is to protect the horse's spine from excessive movement. "The primary role of the back muscles during walking is to control the stiffening of the back rather than to create movement" (Hans Carlson-1979). If the rider's lumbar region oscillates freely as emphasized in the equestrian education, the range of movement of the rider's vertebral column exceeds the range of possible movements of the horse's vertebral column. The muscles of the horse's back react then preventing the spine from the amplitude of the rider's movements. The protective reflex contraction of the epaxial spinal muscles protects the horse's vertebral column from a range of movement that the horse's thoracolumbar spine is not capable to execute.

Harmony between the rider and the horse's back cannot be created via "relaxation," but rather through minute and controlled motion of the whole rider's vertebral column.

"The subtle S-curve of the spine allows the spine to oscillate minutely, a movement so tiny that it is hardly perceptible to the naked eye, producing a "soft" seat. This "soft "seat differs fundamentally from a "doughy" seat, in which we find a spine that is too flexible and allowed to undulate freely in response to the horse's movement." (Waldemar Seunig). The rider's vertebral column is composed of three curves and the forces induced on the rider's vertebral column from the horse need to be absorbed through subtle coordination of the three curves.

The "doughy seat," which is the seat rewarded in the show ring, allows the rider to absorb more or less comfortably the hose's forces but hampers the horse's ability to use his vertebral column efficiently.

"A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it a superficial appearance of being right." (Thomas Paine 1737-1809) Without knowing it, the great American author provides the only reason why the doughy seat remains promoted in the equestrian education. To the contrary, if the rider is in authentic balance, which means if the vertical position of the rider's body is effectively over the seat bones, minute oscillations of the three curves of the rider's spine will create harmony between the rider and the horse vertebral column movement. Once harmony in the amplitude of the rider and the horse's respective movements is created, the horse will prefer to preserve this harmony following minute adjustments in the rider's back. Doing so, the horse will likely use the muscles of the back which are design to resist attraction of gravity and InertIa force.

The first comprehensive diagram of the way the main back muscles are inserted on the horse vertebral column was published by E. J. Slijper in 1946. The diagram presented here comesfrom Slijper's work. The picture illustrates the main back muscles on a horse's vertebral column.

Acting in synchronization, the main back muscles create minute rotation of the individual vertebrae which create flexion of the spine. This is exactly what the horse did when you noticed the two or three steps where the horse appeared to move more freely. (For better understanding of the equine vertebral column mechanism refer to the DVD,Book, What is the Science of Motion.)

In the absolute, these three steps only demonstrated that the horse's vertebral column was able to work. These three strides prompted me to tell to the owner that while there were many difficulties and that the initial working hypothesis might need many adjustments there was perhaps a possibility that the horse's could be reeducated. The horse's owner was a dressage judge and my language was like Chinese considering the principles she was trained to believe. However, her true motivation was to help the horse and she was desperate. Before considering the science of motion, the horse's owner attempted every possible solution. Two veterinarians had examined the horse thoughtfully, did many radiographies, ultrasound, and other examinations of the right hind legs. They did not find any pathological change or soft tissue damage on any joint of the right hind limb. A chiropractor worked on the pelvis. A massage therapist focused on the lumbar region, and the horse shoer had lost his last hair trying to figure how to help the horse. The trainer who was a Grand Prix dressage trainer had observed that the horse's lameness was less visible when the horse was moving faster. The trainer suggested riding the horse more forward. As the horse refused, the trainer decided that it was a behavior issue. Of course they tried different saddles, and purchased every possible joints supplement. The horse was otherwise in very good health but the owner was considering putting the horse to sleep since she could not afford the cost of retiring for life a three year old horse.

The first concept that scientific research teaches is that a negative result is a positive insight. It permits to know that a specific angle of the investigative technique or a working hypothesis is not working. One should not regard the description of the work previously done on the horse as failure. The veterinarian who did the initial examinations as well as the practitioner who gave the second opinion saw movements of the right hind leg during the swing phase that could very well be the indication of hock or stifle problem. They looked under the skin as they should have done and had the integrity to present the results as they were. The chiropractor's eye was attracted by the pelvis because there were effectively signs of pain in the pelvis area. The problem was that it was not the source of the problem and as soon as the horse was back in motion, the stresses reoccurred hurting again the pelvis area. His work prompted us to look in a different direction. The massage therapist observed noxious stimulus in the lumbar region because there was effectively pain in the lumbar region. As it is clearly explained by Pete Egoscue, the site of pain is not always the site of the problem. "Due to the fact that actual tissue damage may not be present in the area of dysfunction, noxious stimulus (pain) is not a consistently direct indicator of the location of the muscular imbalances causing the problem." (Pete Egoscue) The work of the professionals who examined the horse allowed us to further their work looking into different possibilities.

The main issue was the spine torsion but it originated from the elbow rotation. It was necessary to approach both problems concurrently because the biomechanical properties of the horse's vertebral column greatly influence the weight loading the forelegs and no proper muscular work of the forelegs can be done when the front limbs are supporting an excessive weight. The rotation of the elbow was addressed referring to way the equine forelegs are creating adduction and abduction.

"Adduction", which is the action of the forelimb moving toward the median line, is created turning the humerus toward the inside. Such rotation turns the elbow toward the outside.

"Abduction", which is the movement of the forelimb turning toward the outside, is created by an outward rotation of the humerus. Such rotation turns the elbow toward the inside.

Inward and outward rotations do not occur within the elbow joint. The architecture of the elbow is in fact superbly designed for stability as illustrated on this front view.

The articulation of the humerus on the base of the scapula is at the contrary a "ball and socket" type of articulation. This designe auauthoriszes a greater diversity of movements.

Inward and outward rotations of the elbow result from inward and outward rotations of the humerus. On the left side of the picture, outward rotation of the humerus is inducing inward rotation of the elbow. On the right side, inward rotation of the humerus is creating outward rotation of the elbow. On this picture series, the elbow is photographed from behind.

On the right side of the picture, which is giving a front view, "adduction" is created rotating the humerus toward the inside. The left side of the picture depicts "abduction", which is created rotating the humerus toward the outside.

The solution for this horse was therefore to find an exercise that would create maximum adduction, but minimum abduction. The best results were obtained on a circle left at the walk, pushing the shoulders to the inside of the circle. Doing so, the right foreleg had to move forward of the left front leg and toward the inside. Of course, the circle was more like a spiral in. After several strides, it was necessary to come back on a larger circle and execute the gymnastic exercise again. After a few weeks, as the horse was becoming comfortable with the exercise, we attempted a few steps at the trot.

The second most efficient gymnastic exercise with regard to the right elbow was a long half pass left more forward than side way and at the walk. Doing the half pass without going too much sideways created an adduction of the right front leg while having minimum abduction. The progresses of recreating muscle balance between adductors and abductors muscles of the forelegs, were surprisingly rapid. There is a phenomenon often explained in terms of equine physiology and neuro-physiology. The horse's brain protects a problem but does not work to change it. Until somebody purposely stimulates the muscle group which was insufficiently or improperly used, the horse's brain simply does not do it. The exercises stimulated the muscles and they started to function perfectly well.

In terms of the vertebral column, the transversal rotation was more a problem than the lateral bending. Logically, bending the spine to the left should have helped in correcting both, lateral bending and the transversal rotation. I tried to bend the hose's spine to the left but did not get much result. The horse's spine could not bend laterally to the left because the horse's central nervous system was protecting the stability of the spine. The main function of the back muscles is to preserve the stability of the vertebral column. If the horse is used to travel with the vertebral column crooked, the back muscles protect the crookedness. The horse's brain regarded left lateral bending as a treat to the spine's stability. Reeducating a horse demands to understand how the horse thinks. The point is not to judge the horse's thoughts as they are right or wrong. The idea is to respect the particular horse's mental processing and try to analyze his reaction in respect to the way his mind is working.

Asking different degrees of bending to the right, I obtained different degrees of transversal rotation. The rotations were always excessive but the horse was capable of modifying them. As soon as I was aiming toward left lateral bending it was a panic reaction and consequently a protective reflex contraction of the whole spine. I remembered the three steps that the horse gave me when I rode him for the first time and explored the hypothesis that I might have some results asking first for a longitudinal flexion of the spine.

In horses, the compensation mechanism is extremely complex and influenced by physical discomfort, emotions, memories, fear, etc. If one does not have the intelectual curiosity to explore unconventional avenues, one can only submit good horses to opinions and exploit the horses' talent until lameness ends their career.

Retrospectively, focussing on the longitudinal flexion of the horse's spine was efectively the solution. Loocking back, the logic was quite clear. The main function of the back muscles is to preserve the stability of the spine. Stability is a survival reflex and if the spine is twisted and the horse is used to functions with such torsion, the crookedness is regarded by the horse's brain as the stability that the bain needs to protect. From the way the horse thinks, a bad stability is better than no stability. When I asked this horse to change the transversal rotation of his vertebral column bending the spine to the left, the horse's brain viewed my request as a menace for the stability of the spine and the horse worried intensively. Instead, when I asked for a longitudinal flexion, the horse's brain did not felt treated. May be the effort was athetically easier for the horse. Perhaps the fact that the suggestion was made through minute adjustments of my vertebral column instead of legs and hands actions did not pushed the horse's brain into protective mode. The result is that the horse explored the thought that he could follow my back adjustments. In order to do so, the horse straightened his own vertebral column.

In fact, it was easy for the horse to coordinate his back muscles and surprisingly soon, I was able to slow the horse's walk even more and further increase the longitudinal flexion of his vertebral column. As expected, the longitudinal flexion of the horse's vertebral column reduced lateral bending and transversal rotation. Most of the work was initially executed at the walk. Trot departure was asked when the horse was sustaining a good vertebral alignment to the right. As he was no longer in pain, the horse explored the trot departure cautiously but succeeded practically at the first try. This is another phenomenon that we have observed through these "impossible recoveries." Rarely are horses lazy, unwilling, stubborn, etc. They are protecting pain or discomfort. As we suppress the pain, they perform easily achievements that they violently opposed to as they were in pain.

The next step was to ask for left lateral bending. Since the horse had never really trotted before with a rider on his back, I had in mind the idea that he might have less bad memories at the trot. Surprisingly, the horse explored left lateral bending without apprehension. The first lateral flexion was more an impression of lateral bending than a real lateral flexion but in a reasonable period of time, the lateral bending to the left became easier to ask and looking more like a left lateral bending.

At this point, one may want to know more about these rider's vertebral column adjustments that are stimulating longitudinal flexion of the horse's back. In 1964, the author of one of the first dynamic studies of the equine vertebral column mechanism wrote, "An initial thrust on the column is translated into a series of predominantly vertical and horizontal forces which diminish progressively as they pass from one vertebra to the next". (Richard Tucker-1964). The initial thrust on the column is the propulsive force produced by the hind legs. The conversion of the thrust into locomotory force (horizontal,) and forces resisting accelerations of gravity (vertical), is created by the rotations of the vertebrae and consequently the muscular system that is rotating the vertebrae. (For a full explanation see, "What is the Science of Motion" Part I.)

There are approximately 344 articular surfaces in the horse's vertebral column. The overall range of motion of the horse's vertebral column is very limited but the diversity of movements is considerable. "The amount of joint range of motion at any vertebral motion segment is small, but the cumulative vertebral movements can be considerable." (Kevin K. Haussler, DVM, DC, PhD, 1999) Proper functioning of the equine vertebral column cannot be achieved flexing and extending the whole spine between greater engagement of the hind legs at one end and flexion of the neck at the other. The biomechanical properties of the horse's vertebral column demand a subtle orchestration of numerous and minute muscle contraction and compensatory contractions. These multiple, precise, and minuscule muscle contractions create the rotations of the vertebrae that are the starting point of bending, forward movement, balance control, etc. Balance control is achieved through the spine converting the thrust generated by the hind legs into vertical and horizontal forces. This conversion demands a sophisticated coordination between muscles moving, resisting, and stabilizing the vertebrae. Such sophisticated coordination cannot be created through concepts as primitive as driving the horse onto the bit. A more refined and subtle dialogue is necessary and this dialogue is the sophisticated correlation between minute and controlled motion of the rider's vertebral column inviting in a subtle dance, harmonic responses of the horse's vertebral column muscles.

Asking the horse to slow down the movement reducing the motion of the rider's vertebral column invites the horse's brain to use and synchronize the muscle group designed to resist the attraction of gravity and consequently converting the thrust generated by the hind legs into vertical forces. The horse's brain will process this direction, if contradictory stimuli are not confusing the horse's mental processing. In the circumstance, contradictory stimuli would be holding a heavy contact on the bit, or rushing the horse forward. Slow and light is exactly the opposite of conventional views that can be summarized in the formula "push and pull." The fact is that if one consults the classic literature the only reference made to "push and pull" is not a recommendation but rather a warning. "The principles of equitation are simple, but the business of putting them into practice is not simple. The methods used in equestrian art are numerous and varied. Some people have been able to sum them up succinctly and picturesquely in the formula: "Push and Pull." But no great profit, obviously, can be derived from this sally." (Decarpentry, Academic Equitation, 1949) The equine physiology also contradicts the "push and pull" concept. The faster the horse goes the stiffer the muscles surrounding the spine. Speed is created increasing the rigidity of the horse's vertebral column. There is very little chance that the horse's brain will explore more sophisticated orchestration of the back muscles if the horse is urged onto the forehand.

Limbs actions inducing forces on the vertebral column and vertebral column muscles resisting these forces, is the fundamental of the horse's locomotion. The phenomenon occurs in all directions; dorso-ventral flexions, transversal rotations, lateral bending. For simplification, James Rooney analyzed the problem on the level of lateral bending. "The musculature of the vertebral column, particularly the epaxial, resists or absorbs the sidewise forces in order to promote forward movement." This action is clearly apparent at the walk. For example, if the right hind leg is on the ground, the right hind leg will push the axis (the spine) to the left. If there was no resistance of the muscles surrounding the vertebral column, the spine would bend to the left. Since there is a resistance, the axis remains in line converting the oblique force produced by the right hind leg into forward movement.

Once left lateral bending was possible, recreating balance between right and left side of the back muscles was achieved via hours and hours at a slow trot and in shoulder-in.

Full balance between the right and left side of the back muscles was never 100% achieved. The horse was sound and functional and had a good life, but if you look very carefully, you will observe a lateral motion of the neck which was the outcome of a lateral movement of the spine. The horse never fully controlled such motion. I lost contact with the horse shortly after this last video recording. However, confirming the thought that the torsion of the spine was greatly reduced but not fully corrected, the horse had difficulties with the flying changes. Left to right was easy, right to left needed preparation. This observation is one of the reasons why I think that the original accident occurred very early in the horse's life. The whole muscular system was very well established in its abnormality.

Human, as well as equine athletes are commonly inherently dysfunctional. If the education does not analyze and address the dysfunction, human and equine athletes perform below their talent until injury halt their career. "Premier athletes can be dysfunctional. In fact, many of the most gifted athletes are incredibly dysfunctional...The potential benefits of innovative techniques, advanced technology and new training methods cannot -and do not- compensate for dysfunctional athletes' inability to perform to their fullest potential." (Pete Egoscue) While the shoulder-in was abundantly used in the second part of the horse's reeducation, it is not the gymnastic exercise that reeducated the horse. Rather, the horse's education concentrated on the conditions where the benefice of the shoulder-in would be optimum. Judging criteria are limited to the horse's body forming an angle of 30 with the wall and the horse's limbs travelling on three tracks. These judging standards have never been the concerns of Francois Robichon de la Gueriniere who invented the shoulder-in. For this specific horse the angle and the number of tracks were definitively not the priorities. The benefices of the shoulder-in emphasised by Mr. de la Gueriniere are real only when the horse combines lateral bending and proper rotation.Only when the horse spine combines lateral bending and proper rotation

On this picture, right lateral bending of the horse's neck is exaggerated and the weight is obviously on the left shoulder. The horse's vertebral column is working coupling right lateral bending and inverted rotation. In respect of the horse's athletic development, this type of shoulder-in is useless even if the angle is 30º and the horse is traveling on three tracks. The feeling is the right hind leg attempting to move toward the inside of the ring and the weight shifting on the outside shoulder. Holding the horse between the inside leg and the outside rein would satisfy the judging criteria but would not change the vertebral column's inverted rotation.

On this picture the horse is working efficiently on the shoulder-in. The vertebral column combines right lateral bending and proper rotation. The feeling is lowering the inside haunch and the shoulders perfectly vertical over the ground.

The case of this beautiful mare is particularly interesting since she is recovering from a problem of kissing spine that has been create precisely by the practice of shoulder-in and other movements combining lateral bending with the wrong rotation.

"Find the Lameness" is now a DVD. In the series "Educating your Eye", the title of the DVD is, "The horse who could not trot carrying a rider". Writing the report, I realised that more video footage would better serve the practical application of advanced scientific discoveries. Also, while still pictures are explicite, animations explain even more clearly the combination between lateral bending and transversal rotation. The DVD "The horse who could not trot carrying a rider" is now available, I want to thank you for your interest and your thoughts. Take care, Jean Luc |